Archive

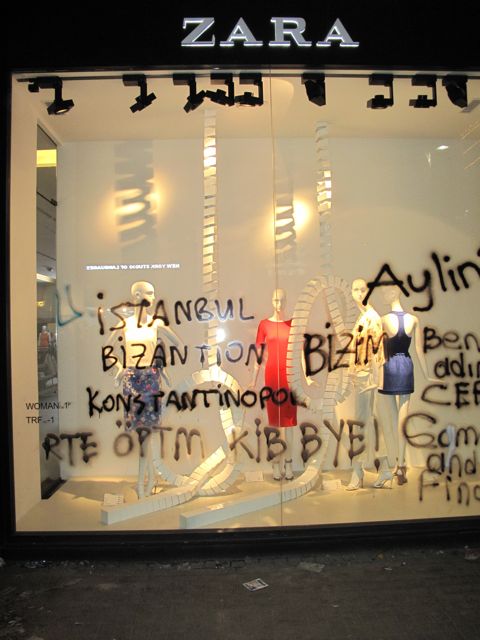

A rich photographic album of Istanbul

Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Waking Up to the Brussels Bombs

The bombs in my new hometown of Brussels didn’t go off close to me. But they did kind of wake me up.

In Brussels airport’s modest departure hall, the explosions were at places I’ve passed through a hundred times over the years. Many of my acquaintances have done so too. The boyfriend of the online editor who works at the desk beside me was on his way to check in, and a colleague was parking her car nearby.

Shortly afterward, a mile away from us, another bomb exploded on a crowded metro train between Schumann and Maalbeek stations, killing 20 people, ripping the carriage into twisted metal and filling the underground with screams and choking smoke. My 12-year-old daughter had taken a nearby metro to school just an hour earlier.

Soldiers have become an everyday sight on the boulevards of Brussels since the November 2015 Paris attacks were traced back to the suburb of Molenbeek.

Brussels is not a big town. My former home of Istanbul has as many people as the whole of Belgium, and it probably takes more time to drive across. As my neighbour said as I met her walking her dog that morning, when something bad happens you always know somebody connected to it. I’m new here, so luckily for me, I knew nobody who was hurt. But my daughter’s schoolfriends did.

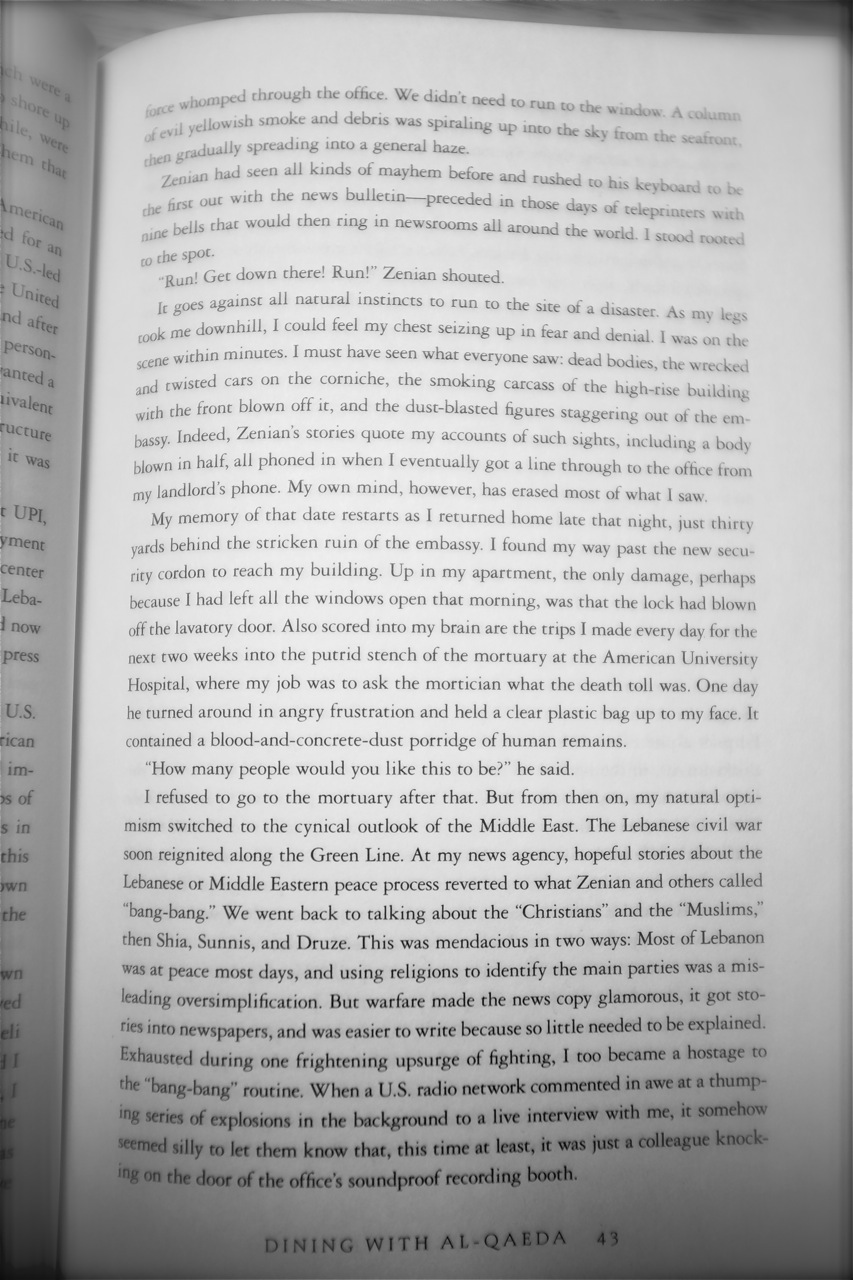

After 33 years living in the Middle East, I’d have thought I was immune to shock. I’ve seen plenty of bombs. My reporting job took me to warfronts, and once trapped me for ten weeks in a Sudanese town under rebel siege. The 2003 car bomb at Istanbul’s British Consulate-General sent its gatehouse up in smoke before my eyes. In 1983 I even witnessed one of the Middle East’s first suicide car bombs, when, as I describe in my book Dining with al-Qaeda, “a shockwave of explosive force whomped through the office … a column of evil, yellowish smoke and debris was spiraling up into the sky … ” (I’ve reproduced the page below).

But somehow these Brussels bombings shook me up, even though I didn’t go near them.

Perhaps it’s because just three days before, an apparently Islamist suicide bomber attacked the Istanbul street where until recently I had lived for 15 years, the latest of several such attacks in Turkey. We could pass the spot several times a day. At the moment of the blast, our caretaker’s son was taking an exam opposite. He sent pictures of what he saw, gruesome, guts-spilling-over-the-pavement images of the four crumpled dead and the stunned gaze of the injured .

Perhaps it was because I thought that by moving to Europe, I was coming somewhere safe. Perhaps I underestimated the angry sentiments of the pro-Islamic State element in the Brussels inner city districts; a journalist friend told me of residents stoning and harassing him as police arrested the organiser of the Paris attacks in the Moroccan district, telling him: “What are you doing? Belgians shouldn’t come here”.

Perhaps it was because I’ve started to identify with one charming Belgium, and have now learned that there is another, less predictable country inside it.

Perhaps my anxiety was also because of the throw-away comments I’ve been hearing in meetings with Western political leaders, or listening to those who mix with them. They are a steady drumbeat of defeatism: “the situation is catastrophic”, “things are out of control”, “my generation was spoiled, and has failed”, or “the crises are piling on top of each other like we’ve never seen before”. After a meeting with the German chancellor during the euro crisis, one German party leader confided that the worst part of it was a sense that nobody knew what to do.

In Brussels on Tuesday 22 March, though, my unease was definitely because I knew I was watching conflict spread. Pale-faced people around me were going through the painful initiation into what what the denizens of war zones have to get used to: calling family and friends as news of real attacks mix with false rumours; discovering the narrow escapes of partners and colleagues; sharing shaken feelings as old certainties crumble; and staying anxious until you learn that everyone connected to you is safe.

Normally, too, my work has long been to pronounce on what’s best for far-away countries. Even Istanbul often felt like a spaceship hovering alongside the rest of Turkey. But on the day of the Brussels bombs, it was reporters from Africa, China, Lebanon and, yes, Turkey, who called up to seek comment on the twin attacks that had paralysed Brussels for much of the day. Perhaps I was still in partial denial about the meaning of the 9 September 2001 attacks on the U.S., and the ones in London, Paris, and Madrid. Now I live here, I get it. The angry Middle East’s conflicts really have gone global.

It’s not only the new reach of the so-called Islamic State that make Belgium feel inter-connected. The country is a famously close neighbour to France, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands. On top of that, my new house in Brussels feels as though it is in the midst of a neo-Ottoman empire, within short walking distance of a Bulgarian cafe, a Macedonian Turkish bar, a Moroccan furniture shop, a Greek corner store, and streets of Turkish butchers, tile merchants and grocers. Beyond them is a veritable casbah of Egyptian, Tunisian, Algerian and other shops spilling their cheap clothing, bedding and wedding finery onto the street.

The languages spoken around me on Brussels trams make the city feel like every nation within a radius of one thousand miles is represented. Forty nationalities were represented among the bombing casualties. Indeed, the refugee influx of the past year is no great conceptual shock. The city is not just the geographic heart of Europe, but in terms of its population, it has Russia, the Middle East and north Africa coursing through its veins.

For me, in short, Europe and the Middle East overlap in Brussels, and indeed in many other European cities. I like Brussels all the more for that diversity and energy, and feel I should understand both sides. As an adopted Middle Easterner, I know the role the West, actively or negligently, has played over the past century in stoking up the mayhem that is now biting it back. And as a convinced European, I wish more could be done to integrate communities that could contribute much in the long term, and in any event, cannot be wished away.

I hope my new European neighbours can learn to feel that way too, and to tell the truth, many of the ones I know do. But for now, violent conflicts, bombings and wailing sirens in the streets are an increasing part of both sides of the Europe-Middle East equation.

—

The page in Dining with al-Qaeda describing the first bombing I witnessed, with my then colleague David Zenian, as a news agency reporter in Lebanon in April 1983:

A Farewell to Istanbul

To say goodbye to Istanbul after 28 years of living in the city, I take one of my favourite walks, from Pera’s Tünel square, wandering down the hill through Galata and then along the Golden Horn sea inlet. For me, this jumble of shops, alleyways and quaysides best conjures up Istanbul’s heady mix of peoples and history: Byzantium, the Ottoman Empire, republican Turkey, and a global megacity on the make.

I head off from my much-loved century-old apartment building, with my wife, my youngest daughter and, passing through like so many others, a childhood friend from South Africa. Some of these travellers are lucky, some not: outside the castellated gateway of my neighbour, Sweden’s two-century old consulate general, Syrians stand in line hoping for visas to Europe.

On the same street, tourists are busily clicking off photos of one of Istanbul’s red and white, Belgian-built electric street tram, restored to service in 1990 and now practically a symbol of the city. We pass by the arches of the Tünel short underground funicular railway, the first metro in continental Europe when it opened in 1875, and still the city’s only real metro in the city until 1999. We continue past the gates of the Galata dervish lodge and its hidden oasis of grand plane trees and mystical whirling.

The main street downhill, named for the 18th century dervish sheikh and poet Galip Dede, is well-cobbled, fitting its new role as a thoroughfare for the more adventurous tourist. The old lamp and car part shops have morphed into outlets for Chinese-made knick-knacks, thin, overpriced hamam bath towels and fresh-pressed pomegranate juice. But many of the old musical instrument shops are still doing well, selling everything from tambourines to white grand pianos and Istanbul’s contribution to the world’s musical vocabulary – the handmade brass cymbal.

Spare parts for almost anything

Half-way down the hill is the noble old stone cylinder of the Galata tower, part of the fortifications that protected late Byzantium’s Genoese colony, topped since the 1960s by a roof in the shape of a pointed cone. Here we part ways with the travellers who are juggling to fit both the tower and their own image into cellphone selfies, and head toward Perşembe Pazarı, a warren of shops that supply Anatolia with spare parts for almost anything.

There are countless places to pause: to trace parts of the pre-1453 Ottoman conquest fortification walls propping up lines of houses; duck into a diminutive early Ottoman courthouse turned aluminium depot; admire the curving street of grand Ottoman banks now becoming boutique hotels, fancy restaurants and cultural centres; and make another attempt to photograph satisfactorily my favourite survivor, a centuries-old stone and brick building colonised by electric motor repair workshops, whose angular first floor rooms jut out into the narrow street.

Toward the bottom of the hill come all manner of premises, from the unexpectedly cavernous to glassed-in cupboards in the wall barely bigger than the men inside them. They display their products proudly: sawblades as big as cartwheels, stacks of metal ingots, rubber seals of all sizes, mammoth industrial fans, and amazing varieties of nuts and bolts. Finally, just before reaching the shore of the Golden Horn sea inlet, a last jumble of ships chandlers sells great chains, yachtsman’s gadgets, and anchors that would take a crane to lift.

I lead our group to a place I’d spotted a few days before. Tables and chairs of a new generation of impromptu and entirely illegal restaurants have for a couple of weeks been spreading rapidly along the Golden Horn’s worn-out parks and quaysides of battered tour boats and fisherman’s skiffs. It looks popular and enchanting, and I want to have my last Istanbul dinner here.

The waterfront is already busy with an organised, illicit chaos. After a few minutes of bobbing and weaving, I see waving arms call us to a miraculous space at the water’s edge. A plaid-shirted maître d’ quickly has us balanced on rickety chairs, sipping Turkey’s aniseed-flavored raki, accompanied by slices of ripe honey melon and a slab of rich white cheese. There is no arguing with this director of operations; from a kitchen that looks better suited to a campsite than a restaurant, we are told that we are going to be served grilled sea bass.

An eternal rhythm of the ad hoc

The pop-up restaurant is the embodiment of alla turca, summing up a city that is so many contradictory things at once. Istanbul’s many beauties are often islands in a sea of concrete ugliness. The new can be piled in layers on top of the deeply ancient. A day cannot be planned and is therefore lived ad hoc; nevertheless, days pass in a rhythm that is apparently eternal. It is impossible for anything to be 100 per cent legal – the jumble of laws is too complicated for that – but a paternalistic, interconnected state discipline somehow keeps everything in harness. And personal touches of generous kindness are an essential oil that helps everyone to survive the increasingly tense pressures of a city with teeming millions of people.

This was the spirit that attracted me to the rough-and-ready city I stumbled upon 28 years ago. Thereafter I made many active choices to stay in Turkey. As a base, Istanbul is the heart of a wide and active geography, and as a home, the country offers everything any reasonable working person could want. The only missing part, perhaps, is something I never asked for: a legal sense of rooted, long-term, rightful belonging. I’d just keep extending my annual residence permit, making the most of life as a voluntary pot plant, always grateful for my place as a foreign guest.

Fasting is Cleansing

Sitting at our wobbly table on the bank of the Golden Horn, a bright star snugly fitting into the curve of a perfect Turkish crescent moon above our heads, I contemplate how much Istanbul has changed. In the 1980s the Golden Horn was filthy, devoid of marine life and reeked of sewage. In winter, the city’s mists and lignite coal furnace emissions used to mix and malinger as thick, sulphurous smog that choked me up as practically the sole, lunatic jogger in town.

Gas from Russia, mostly

Now, the Golden Horn is clear and bridges are lined with fisherman pulling up lines of silvery sardines. Natural gas has cleared the city’s lungs, and recreational walking and running are even fashionable. The city is at last planting some trees and grass, and fixing up the public spaces, even if some renovations are stripping the ancient patina from the city’s finest buildings and making them look like newly tiled public conveniences. Over the water, as for every holy Muslim month of Ramadan, bright lights strung out between the minarets of one of the Ottoman imperial mosques enjoin the population to obey the dawn-to-dusk fast. But now the call to the faithful has an almost health-fad ring to it: “Fasting is Cleansing”.

When I arrived in 1987, there were almost no buildings higher than ten stories and just two five-star hotels: a boxy, cookie-cutter 1950s Hilton and an angular, ugly glass-fronted Sheraton. Now the city has countless luxurious lodgings, from Bosporus-side boutique hotels to restored Ottoman mansions. One financial district has created a completely new skyline half-way up the European side of the Bosporus waterway, and a second one is rising on the Asian side of the city.

Three decades ago, there were no supermarkets at all, and restaurants served excellent but almost exclusively Turkish foods. Shopping was an art-form that required an encyclopaedic memory for what I might find where in the city; the guidebook of the day was like an 18th century Larousse, a jumbled, glossy, barely comprehensible volume that fell apart days after you bought it. Now, sleek new shopping malls reach up to the sky, crackling with brand names and glamorous eateries that attract customers from all over the compass, from Senegal and Riyadh and Paris and Omsk.

Turkey’s new manufacturing prowess has moved it away from the two main exports it had when I arrived: hazelnuts and dried figs. There’s no going back to the days when we huddled for an hour a week to see the outside world on the first live link to CNN on television – complete with simultaneous English broadcast via a radio channel. And I doubt I will ever again see the sour face of the lady at the Istanbul post office’s now defunct “small package service” as she dissected a gift of Swiss chocolates in search of contraband. Turkey feels more and more ‘normal’.

From being a group marginalised by official life, Turkey’s conservative Muslims have joined the consumer mainstream, as shown by this ad in Istanbul airport for a headscarf manufacturer.

A self-conscious separateness

Yet, I cannot believe Turkey will give up on its self-conscious separateness. Even today, with its long Black Sea, Aegean and Mediterranean coastlines, the country can feel like an island, well-deserving its ancient name of Asia Minor. Endowed with water, sun and a vast, fertile hinterland, it has never had urgent needs from the outside world. As with geography, so with politics. Bruised by the imperial carve-up of its predecessor state, the Ottoman Empire, Turkey’s governments and elites still seem to feel safer keeping the world at bay with customs barriers, residence permit requirements and a sometimes prickly, go-it-alone foreign policy.

The Turkey I came to in the 1980s guarded one third of the Cold War iron curtain with the former Soviet Union and its satellites, cutting it off from its natural Balkan, Eurasian and Middle Eastern economic hinterlands. Visitors and tourists mostly seemed to be western Europeans, north Americans and Japanese. International sea traffic on the Bosporus was most often Soviet warships being checked out by the white launch we all called the “CIA boat”.

Now, the Bosporus is filled with oil tankers and freighters servicing the many states of the Black Sea. The tourist crowds have been joined by Russians, Chinese, Balkan peoples, Central Asians and above all Arabs, as befits Istanbul’s historic role as a crossroads of east and west.

The new Istanbul is also huge, perhaps double the size it was in 1987, and an official population of 14 million seems plausible. Hundreds of thousands of people walk each day along Istiklal Street, the boulevard outside my house in the centre of town. If London is the great metropolis at the western end of Europe, Istanbul is the continent’s eastern bookend, making everything in between seem provincial or suburban.

A different set of historical data

The changes are intellectual too. In the early years I learned to bite my tongue on many subjects – whether it was the Kurds (officially “mountain Turks” when I arrived), the role of the military (almost sacred, protected by all manner of laws), Turkishness (ditto), Armenians (victims of a “so-called” genocide), or the Greeks (“spoiled by Europe”). It wasn’t just that I didn’t want to run foul of the law, or offend my Turkish friends. I also came to realise that people educated in Turkey worked from a quite different set of historical data than what I had been taught.

Over the years Turkey found out how others saw it and I learned why Turkey felt as it did about its history and neighbours. Most people stopped viewing me automatically as the agent of a foreign power, and the constant litany of conspiracy theories abated. The Gezi park protests around Istanbul’s Taksim Square in 2013 marked the point where for the first time I felt on the same wavelength with politically active Istanbul, perhaps because this time the young middle class raised its voice instead of extremists from left or right. At last, slogans were actually funny rather than reflecting dark layers of despair, victimhood or oppression. The same social courage guards ballot boxes from tampering at election time, empowers independent reporters to defy sometimes massive government pressures and keeps parliamentary debate alive.

This robust spirit gives me confidence that Turkey will ultimately keep moving in a positive direction. The Justice and Development Party (AKP), which came to power in 2002, with its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, now president, deserve some credit for that. Erdoğan and AKP won legitimate majority governments in three elections in a row. They improved the health care system, built fine new roads and public transport systems all over the country, ended routine torture and broke many taboos in search of the right settlement of Turkey’s Kurdish problem and interconnected rebel insurgency. Of course, AKP got on a train that was ready to leave the station, thanks to reforms that their opponents, including the military, had already put in place to get Turkey in line with international standards.

In fact, despite setbacks in the 1980s and 1990s, Turkey’s defining events were mostly stepping stones towards a future more deeply anchored in the West and European institutions. As a journalist, I reported on the 1987 application to join the European Union, the 1995 Customs Union with Europe, and the 2005 opening of negotiations for full EU membership. The 1999 acceptance of Turkey as a candidate to join the EU was the happiest national moment I can remember in the country, alongside, perhaps, the day a year later when Istanbul’s Galatasaray club won soccer’s UEFA cup.

Even today, despite the love-hate nature of Turkey’s ties with Europe, this relationship remains by far the strongest it has, powered by five million Turks in Europe (compared with just a few hundred thousand expatriates elsewhere), and the fact that European countries are responsible for half of Turkey’s foreign trade and three quarters of Turkey’s inward investment.

A lost sense of direction

For now, though, both Turkey and its European partners have lost their sense of direction. Nobody on either side expects Turkey to join the EU any more. Turkey is abandoning some of the building blocks it fashioned in the hope of a more prosperous, European future: freedom of expression is under attack again, the judiciary is under assault by the government, respect for contracts and the rule of law is slipping, educational achievement remains shockingly low, the 31-year-old insurgency in the Kurdish east is heating up again, and President Erdoğan is wrapping himself in an ever-more authoritarian cloak.

Nevertheless, anyone can still drink rakı on the banks of the Golden Horn. Surrounded by hundreds of others who are enjoying the balmy evening we toast Turkey as the waiter puts a big tray of exquisitely grilled fish on the table. He turns out to be a migrant newly arrived from the southeastern Syrian border city of Mardin and is very happy to have found this job. It won’t be for long, however, he predicts with a certain gloom.

A perpetual roller-coaster of change

Two mornings later I walk down the hill one last time. From a distance I already see the little wooden fishing boats and metal passenger ferries bobbing up and down by the quayside. To my shock, however, the sea front is covered in splintered tables and chairs, bulldozer-churned earth and piles of broken plates. All the restaurants, impromptu kitchens and subdivisions have been smashed. A nearby line of fish merchants, who for as long as I can remember have been selling fresh fish to Istanbullus catching the ferry to the Asian side, have also been levelled. Scruffy kids already are scavenging for anything of value that is left.

“What happened?” I ask one of the plain-clothes young men, apparently from the municipality, who are putting up a fence around the devastated scene.

“We’re cleaning it up, making it better, proper,” he replies.

Another tells the man not to bother with me. “He’s some dirty foreign agent.”

My cheeks and ears burn at the old insult and I stalk off towards the Galata bridge and its warren of shops. I’m also filled with indignation over the random way that the lightning bolt of state-sanctioned destruction has hit a part of town that has given me so much pleasure to live in.

“What on earth happened to the fish market and the restaurants?” I ask the owner of a shop selling batteries, radios and highly realistic air pistols.

“Thank God they took care of those fly-by-night places at last!” he replies. “Those eastern mafia guys were taking over. It was putting tax-payers like us out of business. The state should show who’s in charge.”

Even if I’m pretty sure that in this case the “state” is just the municipality seizing control of a lucrative piece of territory that will be handed out to its own partisan supporters, any anger I have soon seems pointless. A few more exchanges with phlegmatic shopkeepers along the way persuade me to view the debris as typical of a city that is constantly breaking and reinventing itself.

This perpetual roller-coaster of change is part of what makes life in Turkey both exhausting and addictive. By the time I’m back up the hill and home, I am reconciled that there will always be another new pop-up restaurant to try out on some unmarked Istanbul quayside. The trick is only to be able to find it in time.

Note: An earlier version of this article said that Galatasaray won the European Championship in 2000. In fact it won the UEFA Cup. This is the secondary cup competition in Europe behind the Champions League, and used to be called the European Champion Clubs’ Cup or European Cup. Many thanks to Alexis Rowell!

A Dutch bride’s journey from the Rhine to the Euphrates

Sometimes a novel can get across what others’ life is like more indelibly than the best-written news story. That’s certainly the case for the Turkish-Dutch marriage at the heart of Jessica JJ Lutz’s new novel De Nederlandse Bruid (De Geus, 2014). Like good non-fiction, this confident handling of a far-away culture has clearly been years in the making, and the well-told tale transports the reader to the heart of a normally inaccessible group of characters. And at a time when Europe is struggling with questions of Muslim, Turkish and other integration, it neatly flips the debate on its head by following a European migrant into Muslim lands.

The story of ‘The Bride from Holland’ is that of a young Dutchwoman, Emma, an under-employed recent university graduate who decides to follow love and the star of her fate. When her fellow-student boyfriend suddenly has to wrap up his studies in Holland and take over his dying father’s business, she leaves her homeland behind and travels east to stand at his side in his new job: clan lord of a remote Euphrates mountain valley in Turkey’s Kurdish borderlands.

Despite her privileges, Emma soon finds she has exchanged the middle-class comforts of north Europe for hard work, chronic feuding, codes of family honour, everyday deaths, loves, jealousies, suffocating traditions and lies that live for generations — the kind of all-or-nothing society that Shakespeare had to go to mediaeval Italy to find. For days after finishing the story, I couldn’t shake this completely convincing world out of my head, and wished that I could have stayed a part of it for longer.

Here is the video trailer with Dutch endorsements for De Nederlandse Bruid, including this from best-selling Mideast author Joris Luyendijk: “This books grabs you”. The translations of the rest are at the bottom of this post.

The tightly woven plot is seamlessly sustained – a wedding, a murder, a suicide, adultery, treachery, ancient gold, a road, a mountain insurgents’ war and more – without losing any of Turkey’s intimate, audio-visual reality. People live vividly in the present tense, but are unable to cut themselves off from their past. And along the way, a first disoriented Emma is forced to grow up, find herself, and discover that even today, eastern marcher lords and their ladies, like everyone else, have many a dragon to slay before they can hope to secure their realm or riches.

“You really know what you’re talking about”, says presenter Ghislaine Plag. Click to hear 10-minute author interview with Netherlands’ Radio 1 (in Dutch).

A rural community in Turkey is no easy place to discover on one’s own. Much is left unsaid to outsiders, and more drama unfolds inside it than is apparent on the surface of poor concrete houses and chaotic family smallholdings. Jessica Lutz draws characters as they are, without a wasted word or a hint of condescension. The polished plot sweeps smoothly from the Rhine estuary commuter town of Ijsselstein to the ancient hill country of Gerger, which overlooks what is now the huge lake of Euphrates river water backed up behind the Ataturk Dam. The narrative is propelled forward by sharp, gripping dialogue that crackles with humour and cunning.

“Fantastisch, fantastisch” – Dutch radio interviewer after Jessica JJ Lutz reads from her book and talks about Turkey, women and fiction writing (at 2’30”, then jump to 35′ to start hearing extracts).

There’s one such comic moment a series of misunderstandings at the wedding – including a bottle of goat’s blood – when the bridegroom has to exclaim to his headstrong new wife: “Listen, here we don’t get married for pleasure”. Later, hearing tales of past battles when touring their new hardscrabble domains, Emma asks why the village clansmen no longer spend their winters pursuing heavily-armed blood feuds. She is told simply: “There’s television now”. Above all, what comes through is a Turkish Kurd community that is obviously very different in its concerns about religion and honour from Dutch society, but also principally motivated by much the same things as Europeans: power, love, land, jobs, money — and quick illicit profit if it might be got away with.

Lucky Dutch readers, who are already able to devour this novel. Buy it now! And producers of Turkish sitcoms, you need look no further for your next dramatic story. As for those other worried Europeans who struggle to make sense of how their societies are becoming ever-further intertwined with those of their Muslim countries to the east, I hope you will get the chance to read ‘The Bride from Holland’. Europeans are right to be worried by the problems of slow development in their eastern neighbourhood. But there’s a lot Europeans may not know, and above all, do not feel about their neighbours. When they finish a rare book like this, truly and elegantly able to reflect the inner dynamics of Anatolian society, they’ll find that they are a lot less scared.

(This is a version of an article published in Turkey’s Today’s Zaman. For the record: I am married to Jessica JJ Lutz.)

***

De Nederlandse Bruid, 234 pp, was published by De Geus in Breda, Holland in November 2014. Dutch paperback and ebook versions can be bought from the publisher here.

For a cute one-minute music video of authorial book-signing bliss at the SPUI25 Amsterdam presentation of De Nederlandse Bruid, click here.

Jessica JJ Lutz’s blog is here. This is her second novel and fifth book. Her first novel, Happy Hour, published by Conserve in 2009, can be bought here.

***

***

Endorsements and Reviews

“With some thirty years’ experience in Turkey, Jessica Lutz is the Netherlands’ best-informed connoisseur of this region. After her very successful book, ‘The Golden Apple: Turkey between East and West’, she has now turned to fiction. ‘The Bride from Holland’ is not just an exciting book. It lives and breathes Lutz’s deep bond with this land”. – Bram Vermeulen, Netherlands’ 2008 Journalist of the Year and a Dutch TV correspondent in Africa and Turkey.

“‘The Dutch Bride’ grabs you from the first pages, drags you into the claustrophobic isolation of a Kurdish village. Does love really conquer all? You will discover the limits of idealism, good intentions, and your belief that you can do things differently.” – Joris Luyendijk, Dutch anthropologist and best-selling author on the Middle East.

“An extraordinarily stirring and atmospheric book, which intensely brings to life the fragrance and hues of one of the most beautiful places on earth.” – Stine Jensen, Netherlands’ leading television philosopher.

“A thrilling cultural novel, in which the reader cannot escape from their own prejudices. Hooray, that a book this classy can still be written and published! Absolutely worth it: I read it at a gallop from beginning to end”. – Ebru Umar, Dutch-Turkish author, columnist and women’s magazine editor.

“A must-read in which the characters are tangibly real and the raw east of Turkey comes to life. I could almost see the morning light and smell the scent of wild flowers. Jessica describes the traditions, customs and life so vividly that I became homesick for my beautiful, complicated country”. – Fidan Ekiz, Dutch-Turkish television personality.

“Very successful, counter-intuitive and enriching … the cultural-historical background is woven into the personalities, dialogues and plot. In one great, flowing movement you are taken on a journey to an out-of-the-ordinary-world place where, amazingly easily, you can recognise your fellow man”. – Maryse Vincken, De Scriptor, 30 Nov 2014.

“An excellent, realistic, and most of all intriguing story. It’s a contemporary novel full of idealism and dreams, which find traditions and hard life standing in the way, without being unbelievable for a moment. The flowing writing style and the fine exploration of emotions, doubts and threatening situations complete the whole. I enjoyed it and while reading I felt that I was right there in Anatolia … five stars!” – Patrice, Leesclub van lettervreters De Perfecte Buren, 16 December 2014.

“A fascinating book with many unexpected twists and a surprising end … I really recommend it, especially for those who want insights into Turkey behind the scenes, and beyond inter-cultural frictions”. Nikolaos van Dam, former Dutch ambassador to Turkey, Middle East specialist and author.

Turkey’s Taksim Carnival Commune

[This post written on 10 June, the day before the 7am police intervention that took control of Taksim Square, the Atatürk monument and the Atatürk Culture Centre. On 16 June, the police took control of Gezi Park as well. For the aftermath, see below].

I still couldn’t believe my eyes as I wandered this weekend round Taksim Square, along with thousands other visitors who thronged there this weekend to take in this extraordinary moment in Turkey’s political life. Even a few days ago there were just a few people camping out in what was once the small, unfrequented park, from where Turkey’s protests over the uprooting of a few trees blossomed into a national protest movement. A carnival atmosphere has now spread out from the park to include most of the square itself, a fair in which an alphabet soup of often little-known Turkish organizations have set up shop. There are revolutionaries, Marxists, Kurdish insurgents, anti-capitalist Muslims, environmentalists and many, many more.

Like all new-borns, a rush is on to name and define the wave of protests. Are they “a few looters”, in the inimitably dismissive comment of Prime Minister Erdogan? But if not that, then what? A Turkish Spring, a poll tax turning point, an “occupy” movement, Piraten or indignados? A political earthquake, sure, but on which of Turkey’s many fault-lines: secular-Islamist, rich-poor, new urban vs old urban, left-vs-right, Kurdish nationalist vs Turkish nationalist, Sunni Muslim vs Alevi, authoritarian vs anarchist, environmentalist vs shopping mall builder? Of course, the answer is all of the above and all of no one of them. As some leading lights of the small old leftist opposition parties put it, the demonstrators themselves probably have as little idea as the government about what exactly the protests are about. Whatever the final judgment of history, there is already a “revolution museum” in a commandeered hut from the now suspended roadworks around Taksim. And while they wait, protestors take time out at “The Looters’ Cafe and Reading Room”, stock up on supplies at the “Brigand Market”, and get their souvenir stickers from the “Taksim Commune”.

“Don’t bow down” T-shirts being advertised by a penguin on Taksim Sq (a national symbol after a Turkish TV news channel aired a penguin documentary instead of the peak of the protests).

A “Taksim Solidarity Platform” has built a stage in the heart of the park for hosting groups like the “Looters’ Chorus” and is trying to rally its disparate members to agree reasonable demands – 35 groups mid-week, 80 groups now – and its officials rush about in union-style printed overshirts. Merchandising is putting its mark on proceedings: Turkish flags with secular republican founder Ataturk superimposed are popular; a T-shirt saying “don’t bow down” is everywhere; there is also a a scarf demonstrating unity in protest between all three of Istanbul’s main rival football clubs. There are many references to the “looters”, or çapulcu, including a T-shirt with the Turklish phrase “Everyday I’m chapuling”.

This is a rare time in which international media are interested in Turkey as Turkey, not as part of the usual effort to pigeon-hole the country as part of the Middle East, Europe, or the Islamic World. The only other time I can remember this happening is during the massive 1999 earthquake around Istanbul, when more than 40,000 Turks were probably killed and the outside world forgot its prejudices about the country and real empathy was on offer. Similarly, visitors from Europe say the “Occupy” atmosphere is suddenly making Turkey looking very European. Unfortunately, the muzzled way Turkey’s national media initially covered the events was a reminder of the non-European limits Turkey’s places on freedom of expression.

Something in the scene reminds me of the liberated atmosphere in 1996, when the UN’s Habitat Conference was held in Istanbul and Turkey’s non-governmental organisations were allowed to gather in an Ottoman barracks opposite the Hyatt Hotel . The idea of anything being allowed to organise legally outside direct state supervision was then very new (Turkey is still digging its way out from being so long the West’s own East bloc government). It was the first time many of the NGOs were really aware of the existence of other such groups, and all derived a great sense of solidarity as they met and talked. Another comparison would be with the first political chat shows in the early 1990s, when Turkey stayed up until dawn to watch people debating their way out of the country’s old black-and-white, enemy-or-friend view of life.

Today, the whole country is now talking about the protests, the new generation of students who are its leading element, and the way there is a sense of happy, humorous liberation in the air. If only for this reason, I hope the authorities take a European view of this and continue to let this outpouring of democratisation run its natural course in Taksim Square – and that the protestors do find a consensus to take down the barricades, open the square up to traffic and allow all normal municipal functions to resume.

Still, nobody knows how this will end, only that how it ends will define much of the next decade. There are hardline revolutionaries among the protestors’ groups who do want to smash the Turkish establishment in the name of various ideologies. Still, they are far from the mainstream of the protestors, and it seems inconceivable that the security forces should launch sudden violent action against the currently large group of people in the square; yet everyone knows that one day the other foot will fall, perhaps not directly, but indirectly through the ongoing arrest-and-release campaign against social media ‘provocateurs’ or leaders’ public threats and intimidation of domestic and (openly now) foreign media.

The problem for the authorities is that now the protests are not just about Taksim, nor one small social class in Istanbul, nor even Istanbul itself. This movement has taken root all over the country. I was passed on the Istiklal Street pedestrian boulevard leading to Taksim by a band of young men who’d travelled all the way from the southern Taurus Mountains to march to Taksim to protest a dam being near them. And in the working-class dock district of Hasköy, I watched a squad of forty schoolchildren set off for the miles-long march to Taksim with matching blue flags and outfits.

So here are some more photos of the big party, even as we all wonder what form the hangover will take.

A line of stands in Taksim Square in front of the old Ataturk Culture Centre, now a corkboard of colourful protest and revolutionary slogans.

Gezi Park on Taksim Sq is now full of people sleeping in tents, often students, and drew tens of thousands of visitors from all over the city over the weekend.

A pick-up truck overturned in the first night of protests has become a wish-list of protestors’ demands – typically, an end to the concrete covers up 98.5 per cent of the city.

This group arrived in Istanbul from Antalya Province, 12 hours by bus, to protest a hydroelectric dam that will destroy their Tauros Mountain valley.

Sample slogans from the political fair on Taksim Square: “Damn the Wage-Slave Order” (from an organisation called ‘Sweat’); “Against the New Sevres [a 1920 Treaty carving up Turkey by the imperial powers] – Long Live Our Second Liberation War” (from the People’s Liberation Party); “Long Live Revolution and SOCIALISM”; “Political Status to the Kurdish People [unreadable]…Mother-Language [Education]” (from the Freedom and Socialism Party); Hope is in You, the Organization, the Revolution; Forward for Revolution, Socialism or Death” …

The Kurdish nationalist movement has carved out its own corner of the square, where flags showing the jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) are waved as here from an overturned police car and activists dance in long lines.

Left-wing groups are rushing to show their relevance by handing out free copies of their hard-to-read publications against capitalism and shopping malls – here delivered to the Taksim Square in a liberated supermarket trolley.

Merchandising the revolution: The “We are looters but we feel good about it” scarf scores points off Prime Minister Erdogan’s dismissive labelling of the protestors

Paper hot air balloons lit with big candles float into the air each evening from Taksim Square, here seen rising over the 19th century bulk of Istanbul’s Russian Consulate-General.

POSTSCRIPT

The day after these photos were taken, on June 11, the police pushed the protestors off Taksim Square. The protestors responded with stone throwing, fireworks and in the case of one small group, Molotov cocktail throwing. The police then used high-pressure hoses and tear gas and tore down flags and banners. The police said they wouldn’t intervene in Gezi Park itself, but eventually, on the evening of June 16, they pushed them out of there too. Both sides accused each other of bad faith – the government saying protestors gave into radicals who only wanted a fight and refused to leave the square, and protestors who said they needed more time and commitments from the government. Once again, the police used force and tear gas in overwhelming measure. Protestors tried to win back the square on June 17, when the photos below were taken, but the police took strong measures to prevent that happening.

A tough column of protestors from the Turkish Communist Party moves through Nevizadeh restaurant street after a confrontation with police.

Middle-class girls fix their anti-gas gear as they try to find a way past police lines to recover Taksim.

The Turkey protests – aftermath or interlude?

The world’s media has descended on Istanbul to find out more about our Turkish unrest, an extraordinary long weekend in which the secular middle class lost its complacency, overcame its fears and discovered political protest. A new sense of humour joined the usually stern-faced national narrative, people are somehow walking taller and it is amazing to hear great, spontaneous waves of clapping spreading among pedestrians walking up and down Istiklal St outside my house. Everything changed, even if the baleful music from the music shop opposite unfortunately emerged from the day of rioting stuck the same gloomy rut (Ol-muyooor, ooool-muyor, “It just isn’t happening…”).

The analysis is flowing fast. Here are just some good pieces in English I saw flashing past: Frederike Geerdink in Diyarbakir excellently explained why Kurds feel detached from the Istanbul excitements – a perspective that shines light on where Turkey as a whole really is today. Piotr Zalewski gave a fine account of the big day on Taksim. Henri Barkey pointedly noted how much he thinks this is about Prime Minister Erdoğan and his “yes men”, and the sharp wit of Andrew Finkel laid out how the PM needs to open up to local involvement in local decisions. Claire Berlinski’s acid take is a bracing antidote to mainstream news on Turkey. Nadeen Shaker had a fascinating interview with a perceptive activist, Ozan Tekin, about what the Taksim Square protests do and do not share with Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

At Crisis Group’s Istanbul office, we couldn’t resist adding our voice to the hubbub, putting together what we hope is a balanced distillation of how we find ourselves answering questions from the sudden inrush of new and regular visitors. You can find our “Turkey Protests: the Politics of an Unexpected Movement” on the Crisis Group website here. I also did a commentary for Bloomberg urging Mr. Erdoğan to engage the protestors. Watching the novel, calm, empathetic outreach of Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç at a news conference on 4 June, I felt that if Prime Minister Erdogan can execute one of his famous U-turns and do the same, it would do much to absorb the tensions.

I also attach some images from the scene on Taksim Square and Gezi Park, mostly from Monday 3 June. The upbeat mood was much the same in most places in Turkey. The country is an amazingly resilient place that actually enjoys a good crisis – it’s normality some people have trouble with! Still, ordinary folk are almost competing to get things ‘back to normal’ wherever they can by cleaning up and fixing the few broken shopfronts.

Still, nightly police-protestor confrontations that last for hours on the front lines have been frighteningly violent at barricades in Istanbul’s Beşiktaş district near the prime minister’s office, and in central Ankara. The new slogan rolling up from my street last night was a boisterous one: “Tyrant, Resign!” So for now we wait for the prime minister to return from his north African tour, and to discover whether we are now looking at the aftermath of an emotional outburst of popular sentiment, or whether the current precarious stand-off is just an interlude.

Where it all began – the corner of Gezi Park on Taksim Square where an excavator’s attempt on May 27 to clear space for a new pedestrian pavement brought a group of environmentalists to protest – and where, when police intervened by burning their tents and tear-gassing them, a national movement was born. (The plan to build a shopping mall on the park is real but was not actually why the trees here were going to be uprooted).

While protestors in Taksim largely avoided looting and vandalism, they did target the work machinery for the new underground tunnels in Taksim Square, a first stage in the government’s top-down redesign of modern Istanbul’s most important public space.

An overturned police car on Taksim Square. Not many vehicles were wrecked like this one in the first days, but Interior Minister Güler said on 6 June that by that time a total of 280 workplaces, 103 police cars, 259 private cars, one house, a police station, 11 AKP political offices and one CHP political office had been damaged.

Another overturned car on Taksim Square, quite a contrast to a typical group of well-brought-up girl protestors, wearing the signature black of the protests.

This group of high-school students in Taksim Square’s Gezi Park skipped class for the third day to follow the ebb and flow of protest (and didn’t tell their families where they were off to either).

University students moving off to man the barricades after singing and dancing under the trees of Taksim Square’s Gezi Park.

Turkey is a resilient country and people quickly sought to take advantage of new opportunities – here a man finds a market for surgical masks protestors use to protect themselves from tear gas.

![The big clean up by the shops on the central pedestrian boulevard of Istiklal St. was particularly swift and impressive. The biggest problem was graffiti everywhere - some of it injecting an unusual sense of humour: "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" (a dig at mainstream media failure to cover much of the protests), "This country is beautiful when It gets angry", or "I've been a faggot for 40 years, but I've never seen [unprintable]".](https://hughpope.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/img_75892.jpg)

The cleanup by shops on the central pedestrian boulevard of Istiklal St. was particularly swift and impressive. The biggest problem was graffiti everywhere – some of it injecting an unusual sense of humour into Turkey’s often self-important politics: “The Revolution will not be televised” (a dig at mainstream media failure to cover much of the protests), “This country is beautiful when it gets angry”, or “I’ve been a faggot for 40 years, but I’ve never seen [unprintable]” (More here).

Istanbul’s demonstrators celebrate victory in Istiklal and Taksim Square

At dawn of the morning after the night before, a flock of pigeons was picking on the debris from an amazing 48 hours outside my home on Istiklal St, the pedestrian boulevard through the heart of Istanbul. It was littered with trash, broken beer bottles and the odd ornamental tree yesterday’s protestors dragged into the middle of the road to act as a barricade against police forces. A few stragglers were still drifting away from a boisterous all-night celebration in Taksim Square of what they see as their victory over the police and government. Protestors and police apparently have clashed again briefly in at least one place elsewhere in the city, Beşiktaş, but for now things are quiet here, although a tang of tear gas lingers in the air.

By 10am this 2 June, municipality cleaning trucks had got most of the street clean. Vans are coming to restock shops – or perhaps to see if the shops survived. Every few minutes in the blue sky above us, as they did even when clouds of tear gas billowed down the street during the battles yesterday, passenger planes make their final approach to Istanbul airport. But absorbing what happened on 1 June – and getting back to business as usual – is going to take a while longer than that.

What are the long-term implications of having the heart of Turkey’s touristic, commercial and cultural capital captured by young people walking up and down most of the night shouting to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan: “Tayyip, Resign!”? How impressive is it that these demonstrations spread to half of Turkey’s 81 provinces? Is this the beginning of a new democratic era of brave youth confronting an inflexible authority, or should we focus on an early taste of some frightening anarchy and looting? How much real political water is there behind this dam burst of secular sentiment in Istanbul, a flood which swept the flags of innumerable marginal and not-so-marginal left-wing groups to the heart of Taksim Square? How did a polls-obsessed government misjudge the mood so much? Does an ideology that consists in part of turning Turkey into a country in shopping malls linked by dual-carriageway highways not satisfy the people?

I’m not yet sure about all these big questions, except to note once again that the government still won power in 2011 with 50 per cent of the vote, that it did not order its own probably far more numerous supporters out onto the streets of this city of more than 10 million people, that its cementing over of green spaces is nothing new in Turkish urban planning, and that under this administration, the parks and roadside flowers have looked better than anything previously. And for once in the first three days of the demonstrations themselves, the security forces and police, however excessive their use of tear gas and despite more than 100 people injured, miraculously killed nobody.

So while thinking about those big unknowns, I think I’ll just share some pictures from the Istiklal St scene at about 11pm last night.

Amid plenty of superficial damage and cracked display windows, the only shop on Istiklal I saw that was truly pillaged was the pastry shop owned by Istanbul Mayor Kadir Topbaş

This prortestor wore her horse riding cap to the demonstration – for all the left-wing party flags, most of the protestors seemed to be middle class folk.

Protestors seemed particularly focused on attacking and breaking up the worksite for putting Taksim Square traffic into tunnels – presumably seeing it as part of the shopping mall complex that the government is still intent on building in some form on the Gezi Park in Taksim.

The door of the French Consulate-General near Taksim. Here a slogan in French declares “Poetry in the Street – 1 June 2013”

A group of protestors clap as an old man draws a picture on the wall of the Paşabahçe glassware shop of republican founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Many left-wing slogans appeared on the Istiklal St. shops’ blinds – here ‘Death to Fascism, the only way is Revolution. (Signed:) The Bolshevik Party”

A ringside seat as Istanbul protests

Living right on Istanbul’s main pedestrian boulevard of Istiklal St, 1km south of central Taksim Square and the now legendary Gezi Park, has given me a ringside seat to the wave of unrest that has gripped the city over the past 48 hours.

At times everything seemed normal, even if the passers-by were fewer than on a usual weekend. Until late last night the music shop opposite was still churning out its usual Istiklal St. dirges. Then a group of protestors entered stage right, retreating from Taksim (slogans included: “We are the soldiers of Mustafa Kemal [Ataturk]”, “You’re all sons of whores”, “Government Resign”, “Shoulder to shoulder against fascism”…), the first of several waves usually pursued with a strange theatricality by a group of police with an ugly water cannon truck — water from its high pressure hose scattering people like the whip of an angry mythical beast – and a posse of riot squaders. A few explosive pops from the tear gas launchers, and gas would stream out of canisters where they landed, the smoke unfurling in ribbons down the street. At our third-floor height it usually only burns the eyes and nose. We closed the windows for a few minutes before opening them up again for a better look at the next wave of attack and counter-attack.

Early this morning, all seemed quiet. Municipality cleaning trucks had left the pedestrian precinct immaculately clean, the vans that restock the Istiklal St. shops turned up, and middle-aged north American tourists wandered down in new white sneakers & their pink, plum, and orange cottons, taking in the sights. But there was an odd silence in the street that did not bode well for the day ahead.

At 10am, a first group of protestors came running down the street, chased by another police patrol spraying water left and right, popping off gas canisters and chasing demonstrators into side-streets. One group who took refuge in a shop got a special, almost casual gassing by passing police. At 10:30am, small groups of demonstrators gathered again. One came from the south, built a barricade outside our building to try to stop the police vehicles chasing them, and then headed off for Taksim. Throughout this, the seller of Turkish simit sesame bagels from a little red nostalgic ‘Beyoglu’ cart remained firmly at his post – doing steady business just meters from where the skeins of gas fumes were floating around. But even he fled at 1:15pm, when the police charged more strongly and fired a dozen gas canisters, some aimed high and sent spinning down this late 19th century boulevard like javelins on a battlefield. Everyone scattered into sidestreets. (My wife Jessica Lutz filmed it, here). Ten minutes later, they were back with even more people filling the pedestrian district, with even more scornful slogans about “Killer AKP” (the ruling party). At 2pm, the police counter-attacked, even more dramatically. The crowd regrouped, its slogans turning into low howls of anger; at 2.45pm the police pushed back again from behind a thick screen of gas. This time they also faced a barrage of stones from some protestors, among the very front lines of which could be seen the red flag of the Turkish Communist Party and even a lone flag of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

At 4pm, after a last flurry of gas canisters near Galatasaray, the police reportedly received orders to allow demonstrators through to Taksim. Gradually the crowd – mostly cheerful, ordinary folk with no obvious political affiliation who filled the breadth and length of Istiklal St’s southern half – moved forward to Istanbul’s central square in celebratory mood.

So what’s new in all this? Social media, for a start. Many of my Turkish friends are glued to their Facebook accounts, sharing pictures of the worst police outrages – a remarkable one shows a policeman dousing a protestor with a device like an insect spray gun, as the protestor holds up a sign saying “Chemical Tayyip” [Erdogan] — and spoof posters like an ad for the “Istanbul Gas Festival”, “We can’t keep calm, we’re Turkish” and so on. The spontaneous look of the small groups of protestors coalescing and dispersing in the street outside is quite unlike the usual formal protests organized by unions and political parties, and lacks the angry, violent edge to the pop-up parades by radical left-wing groups. Mostly young and middle class, they include people in shirts for all Istanbul’s big rival football clubs, young women in headscarves, groups of white-coated medical volunteers, and a young man with a big bag of lemons, selling them to the crowd as an tear gas antidote.

On the other hand, Turkey had the same banging of pots and pans in anti-government neighbourhoods in the 1990s, which was widespread on the Asian side of Istanbul last night; and in my district of Beyoglu, every year or two a big issue brings angry demonstrators and policemen with gas weaponry that is used to clear people away. While the government is clearly rattled this time round, after four days, perhaps the only obvious long-term political consequence I can predict so far is that all this will be remembered when Prime Minister Erdogan launches his expected quest for the presidency in an election next year.

The demonstrations are already about a lot more than sympathy for condemned trees in a street-widening scheme at the Gezi Park, and have taken on a distinctly anti-government tone. Reasons for the protests I’ve heard from friends over the past 48 hours include: a reaction to the ruling party’s focus on building shopping centers everywhere, even in Istanbul’s last patches of green, like the future mall planned for Gezi Park; how the half of the population that didn’t vote for the government resents what it sees as its increasingly high-handed, majoritarian, we-know-best style; among secularists, a sense that the ruling party revealed a Islamist agenda that could infringe its lifestyle with sudden new regulations this month on alcohol consumption (my blog on that here); among the 10 per cent Alevi minority, anger at this month’s choice of Ottoman Sultan Selim the Grim’s name for a third bridge over the Bosphorus, since he killed many Alevis; the general feeling that there is little transparency in what the government plans and does, and that the media is under great pressure not to discuss real events or who benefits financially from projects (one mainstream TV program during last night’s was about radiation on Mars!); and above all, a sense of powerlessness, and frustration at the inadequacy of the main political opposition parties, which have left the bulk of secularists of Istanbul with a feeling that they’ve had no real political representation for years.

There’s a lot of talk among my Turkish friends of the Gezi Park demonstrations being a “turning point”, and today it feels that way, with growing numbers of demonstrators in the streets, many cities in Turkey protesting in sympathy, and the unscripted nature of proceedings. Normal patterns have been drastically changed in recent days, not just in traffic but also in many peoples’ lives. Phone calls with friends in the center are often about “my street is all mixed up now, can’t talk for long”. If anyone gets killed, rather than 100 or so already injured, that will sharply escalate the situation. Here’s hoping the government manages to handle the next 24 hours more sensitively than the last. A good first move would be to get some traction by letting state television give a full version of events – currently, people are consuming a diet of wild rumors and partial views on social media, which can only add to the current escalation.

Of Istanbul caught between West and Middle East

Turkish men dressed in chadors get ready for the ‘Hands Off My Porn’ protest against internet censorship on Istiklal St in Istanbul, 2011

Outside my window overlooking Istanbul’s main pedestrian Istiklal St. rowdy recent demonstrations have given vocal testimony to the fragmentation of Turkey’s self-image between the West and the Middle East: secularists condemning America, Islamists condemning Russia, others decrying Syria, Israel, Kurdish insurgents, the ruling government in Ankara (and lots more besides, see right). At the same time, Istanbul is also acting as an incredible magnet for a new generation of young adventurers from Europe, America and beyond.

This new diversity of Istanbul has a digital dimension too. The term “expat” makes my orientalist toes curl, but it took breakthrough expatriate website Istanbul Eats to catch the spirit of Turkish street food , and a new launch, Yabangee (from the Turkish for ‘foreigner’, yabancı), seems to me to be the first English-language publication ever to be written entirely by and for the city’s English-speaking residents. (A true mirror to the narcissism of Turkey’s political culture, Turkey’s English-language newspapers are mostly translated from Turkish source material, and, remarkably, most of their readers are actually Turks seeking to improve their English). Anyway I hope their enterprise fares well and here’s my interview with one of Yabangee’s up-and-coming editors:

Expat Interview: Hugh Pope, Crisis Group Writer and Author of Turkey Unveiled

“People are always asking ‘Where’s Turkey headed?’”. Author and journalist Hugh Pope and I are sitting in one of Beyoğlu’s packed bars, and he’s shouting so that I can hear him above the almost deafening combination of music and chatter. “But I’ve stopped worrying,” he continues. “Turkey is Turkey – and it will just carry on being itself.”

Pope certainly is an authority on the subject of Turkish politics. He’s lived in Istanbul for 25 years and speaks fluent Turkish, in addition to the Arabic and Persian he picked up while at Oxford University. He first came to Istanbul to work as a journalist in 1987, but had visited Turkey a few times before, first as a student in 1980 and on breaks from Middle Eastern conflicts. “After so long, do you become Turkish?,” I half-jokingly ask. “No, you become a sort of semi-Levantine!,” he replies.

A British national but born in South Africa, Pope never really felt at home in England after moving there aged nine. “When I left university in 1982 there was a deep recession, and it was difficult finding a job,” he explains. Yet I suspect he’s making excuses; he probably would have been eager to leave even if the economy had been stronger. “I was offered a job working as a journalist at the Tehran Times, but I couldn’t get a visa”. Rather than return to London, Pope booked a one-way ticket to Syria, aged 22.

He covered the region working as a freelance journalist until, in 1987, Reuters offered him a position based in Istanbul. “They put me in this amazing flat in Arnavutköy, overlooking the Bosphorus.” But it wasn’t all positive. The traffic at the time was terrible – worse than it is today, he tells me – and the brown coal pollution in winter was so bad that sometimes you couldn’t see more than a few metres in front of you. “It was like the London smog of the 19th century,” Pope explains.

Leaving Reuters in 1990, Pope returned to freelance work. “During that time I worked for a range of media; the Independent [a British newspaper], the BBC, the LA Times, and the Wall Street Journal.” But it was with the Independent that Pope felt he could write stories as he wanted, and he leapt at the chance when the paper retained him as a nearly full-time Istanbul correspondent in 1992.

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s there was a lot of coverage on human rights and other ‘bad news’ stories, so Pope would look for more positive stories to try to break up any negative stereotypes. And life as a foreign correspondent was certainly busy, especially since, before live TV news, seeing things mattered. “Once I went to Ankara twice in one day,” he tells me. “That was when Turkish Airlines gave journalists flights for $30. I went out to do a story in the capital, then there was a bomb in Istanbul, which I raced back to cover, before heading back out to Ankara”.

I ask him whether he ever thought of leaving Istanbul. He not only thought about it, but did leave; it was 1995, and he left Turkey to return to South Africa as the Independent’s correspondent. But the move didn’t bring what he was looking for, and so he returned to Istanbul three months later.

“I came back with a contract to write a book about modern Turkey, which I did with my ex-wife Nicole. I loved the chance to research for that book, reading for a year.” The result was Turkey Unveiled, which was recently released in its fourth edition, is an account of Turkey’s politics from Atatürk up to the present day. What was it like to have co-authored a book? “We shared the same views on Turkey so it was no problem. And we had a great editor; the text flows even though there were two authors.”

Turkey Unveiled was first published in 1997, following which Pope started an eight-year stint working full time for the Wall Street Journal. The thoroughness of their editing came as a shock. “Americans are much harder working than Brits,” he says. “And they’re obsessed with getting every factual detail. But the editing process did sometimes remove nuance, ‘flattening’ the articles.”

But it was a positive experience, and Istanbul was his base for covering, at one point, 30 countries in the region; at least, up until the Iraq War in 2003. Pope says he lost heart covering the story, and that the Journal’s editorial pages went ‘war mad’. “I became disillusioned,” he explains. By 2005, he had become fed up with traveling to the Middle East to write stories in which the American audience expected a viewpoint that Pope found it increasingly difficult to deliver.

Pope took an unpaid year off, and got out of Istanbul. With his wife Jessica Lutz, a Dutch novelist, he built a house in the mountains above Olympos, in south-western Turkey, expecting to have the option of returning to work at the end of the year. However the Journal had other ideas. Following a downsize, the job was no longer there and he was demobbed with a half year’s pay.

But as the saying goes, it’s darkest before dawn. The negative stereotypes of the Middle East that had formed since 9/11 gave Pope the inspiration for his next book, Dining with Al Qaeda [published 2010]. This memoir brought to life his Middle Eastern adventures; in one instance, Pope had to ‘argue’ for his life with a Saudi cleric who had tutored several of the 15 suicide bombers of 9/11. That Pope is still alive today is surely testament to his Arabic skills. But the fact that he then made friends with the cleric and took him out for a Chinese meal in Riyadh makes me think there’s more to Pope than meets the eye.

Nowadays Pope seems content with life here in Istanbul. But the pace hasn’t slowed. Since 2007 he’s been the Turkey / Cyprus project director for the International Crisis Group, which seeks to prevent worldwide conflicts. Does have he have any thoughts of England? Pope, “the semi-Levantine”, threatens to visit his brother in the South-West of England, where he went to school. “I love the countryside there and I keep promising I’ll visit soon. I have to take up a voucher for a free lesson at Sherborne’s croquet club”. But I can see he’s in no hurry.