Rulers in many countries are struggling to meet public expectations. Elections fail to produce stable governments. Disinformation spreads alienation. Selfish hierarchies hollow out law and tradition. Trust in elected politicians plumbs new lows. Authoritarian ideas and leaders fill the void.

Surprisingly few people, however, question the electoral systems that are a central part of the mess. What can the partisans of citizens’ assemblies – and other deliberative, participatory, broad-based ways of public decision-making – do to persuade other people that their form of democracy offers a better way to run our lives?

The scale and urgency of the challenge was a defining theme when, for a week in Brussels this October, I joined 270 fellow members of the international movement to develop such a new constitutional architecture. It was the biggest meeting yet of the Democracy R&D network, which has grown by leaps and bounds since 30 people founded it in Madrid just seven years ago.

These activists mostly seek to develop and popularise the use in public decision-making of citizens’ assemblies. Like juries in courts of law, these assemblies are groups of everyday citizens – from a dozen to 200 people – who are chosen by lot to find a solution to tough local or national problems. They meet for several days over weeks or months, are briefed by experts, deliberate on what they hear and take votes on the best way forward. None are exactly the same, but most follow the same principles. A typical template is this one by DemocracyNext, a non-profit on the cutting edge of international thinking on the topic.

Exponential growth

Citizens’ assemblies have grown fast since the first of the modern era was held in Vancouver, Canada, in 2004. The movement lost count of the total after the number reached 713 in 2023, but for sure their spread around the world has continued exponentially. For instance, 51 new citizens’ assemblies were held in 2024 in Germany alone.

Citizens’ assemblies show a way out of the deepening paradox in countries ruled by elected governments. An average 63% of adults in 12 high-income countries are dissatisfied with the way democratic governments are working, a figure that has steadily risen from 49% in 2017, according to a Pew Research poll from June 2025. The paradox is that 77% of adults told a separate 2024 Pew poll of 24 countries that they are convinced that elected governments is basically a good system.

The movement for deliberative democracy, by contrast, maintains that squabbling political parties, polarised societies and self-centred leaders are not bugs that can be fixed, but fundamental flaws of the electoral system. This idea is gaining ground, despite people’s paradoxical faith in voting for representatives. An average 70% of people, the 2024 Pew poll showed, now also think of direct democracy as good (defined broadly as when “citizens, not elected officials, vote directly on major national issues to decide what becomes law”).

In the UK, more than half of respondents from all four major political tendencies told an April 2025 YouGov poll that they would trust members of a citizens’ assembly more than members of parliament to take a policy decision in their own interest.

Looking back with pride, Anthony Zacharzewski of the Brussels-based non-profit Democratic Society told the Democracy R&D conference of the change since he started out more than a decade ago. Back then, in “every conversation I had about participatory democracy, the question was: ‘What is participatory democracy?’ …. We really had to knock on every door. Now the phone is ringing and people come to us.”

But the new democrats have by no means won the argument. The 2024 Pew poll showed there is also clear support for top-down, non-citizen-based alternatives. 58% of people favoured rule by experts, 26% rule by a strong leader and 15% rule by the military. And to judge by myriad speeches, workshops and dinners at the Democracy R&D conference in Brussels, the deliberative movement still needs to find more internal cohesion, popular traction and funding.

Barbed wire can’t protect a house from rotting within

Since last year’s Democracy R&D conference in Vancouver, the electoral success of Donald Trump in the United States has fanned fears that autocratic rule is running away with the race. Alarm has grown over the rise of the authoritarian right in Europe, and the multiple failures of several traditionally strong north European powers to form stable governments after elections.

Zacharzewski pointed out that President Trump’s elimination of USAID and all its funding programmes meant that in a developing country like Kosovo, two thirds of the people working on democracy lost their jobs overnight. “This is repeated right away across the world, even in Europe, where national governments are making similar cuts,” he said.

Recently, too, European states have prioritised defence, not governance, throwing new resources into drone technology, cybersecurity and military spending. For instance, the European Union is proposing to quintuple security spending in its next seven-year budget starting in 2028. Several speakers at this year’s conference worried this neglected improvements to democracy – a domain that, in theory at least, gave Europe its competitive edge in the first place.

“A strong defense on the outside of Europe, protecting a weak democracy on the inside, is asking for problems,” David Van Reybrouck, the Belgian writer, poet and political philosopher told the conference-goers. “We’d be repeating on a continental scale what has happened in Israel on a national scale. A dilapidated house [won’t repair itself just because] you put some barbed wire around it.”

Just €3.6 billion in the EU’s next €2 trillion budget is earmarked for democracy-adjacent activities. Conference speakers urged activists to work harder on getting more funds directed towards democratic innovation. This includes not just citizens’ assemblies but developing ideas like participatory budgeting (allowing groups of citizens a say over part of a government budget), using artificial intelligence to reduce the cost and increase the efficiency of assemblies, and multiple choice “preferendums” on new policy instead of simplistic and easily politicised yes-or-no referendums.

As it happens, the EU has just held a randomly selected citizens’ panel (its name for a citizens’ assembly) on what priorities should guide the budget. Ironically, the 150 citizens did not explicitly recommend the funding of more citizens’ panels.

Still, the first of the seven EU citizens’ panels organized since 2021 did recommend that citizens’ assemblies should be encouraged. The citizens allotted to the latest panel also said the format represented the EU well and that they were satisfied by the experience of democracy by lot. As for stronger defence, the panel ranked it only seventh of their 23 priority recommendations (healthcare, youth jobs and infrastructure spending came out on top). “Very quickly, we realised these discussions are incredible,” an EU budget official who attended the panels told our group. “You can ask more from citizens and trust them more than most people think.”

The European Commission wants to hold more more citizens’ panels. It invited democracy conference attendees to meet members of its panel held in 2023 on tackling hatred in society, some of whom are still involved in briefing EU officials on their findings. As one EU official from the directorate general involved said to the deliberative democrats: “We found common ground. We were amazed by the [panel’s] recommendations. We are advancing on those.”

Breaking through

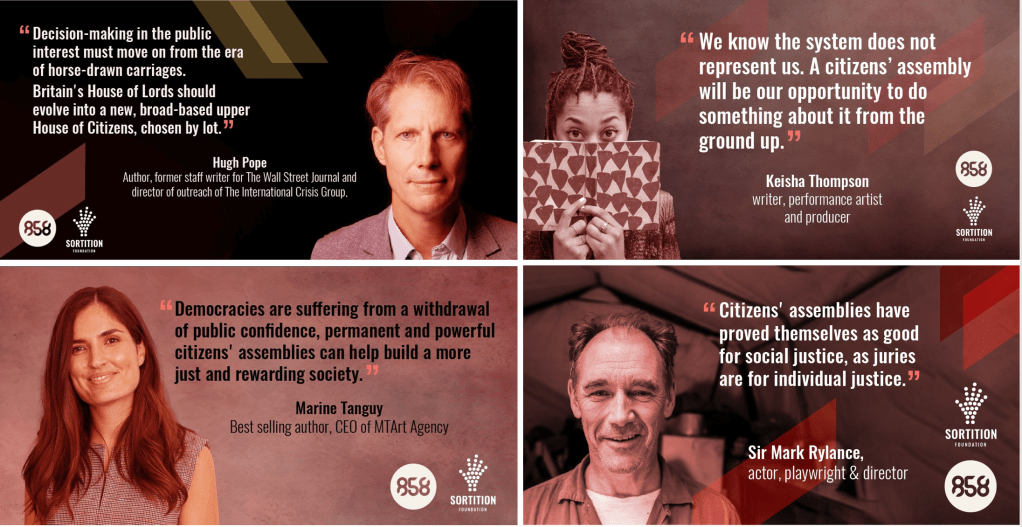

The growing number of citizens’ assemblies being organised by powerful entities like the European Commission, Germany’s parliament and France’s President Emmanuel Macron is not the only good news. More and more thoughtful celebrities are also ready to endorse them. From the English-speaking world, these include author and comedian Stephen Fry, political podcaster Rory Stewart, the late UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, British actor Riz Ahmed and cookery author Delia Smith.

Even India’s Mahatma Ghandi would count as a supporter, according to a conference speech by Yves Mathieu, head of French citizens’ assembly organiser Missions Publiques. He pointed out that Ghandi defended a democracy of directly participating citizens when he said: “If you do something for me without me, it’s against me.”

Many at the conference said the deliberative democratic movement, having devoted its early attention to conceiving and building a new model of doing democracy, must now focus more on mobilising this model to catch up with autocrats and oligarchs. “The sector of deliberative democracy is obsessed with design,” Van Reybrouck warned. “Design matters, but we cannot afford to stay and to remain nerds only. We have to become campaigners as well.”

One sign of new activism is the Sortition Foundation‘s new campaign in the UK for a randomly selected citizens assembly to take the place of Britain’s antiquated House of Lords. But public advocacy on this scale is still a rare initiative, given the cash-strapped nature of most democracy non-profits.

At one conference workshop – on citizens’ assemblies organised without an official mandate – we dove deep in search of new ideas. One of the organisers was Sofie Furu, of Norway’s SoCentral non-profit, which this year joined several Norwegian civil society groups to organise a major citizens’ assembly on the country’s oil fund.

“We know that [the citizens’ assembly model] works, we have seen the magic. But autocrats are way ahead in the communications game and we need to stop being a nerdy little club,” Furu warned.

Ideas to do better voiced during our workshop included these suggestions:

- Streamlining terminology, since the meaning of words like sortition are obscure to many

- Bringing more coherence to the mosaic of organisations working for more deliberative democracy

- Writing into national laws and constitutions the role of and resources needed by citizens’ assemblies

- Spending more time and effort convincing politicians that citizens’ assemblies can help achieve politicians’ own public policy goals

- Outreach to ordinary people along the lines of the Camarados and their “public living rooms”

My personal favourite, suggested by another participant at my table, was to add the simple tagline “Get lucky!” when using the phrase “citizens’ assemblies”. It captures the inspiring sense of empowerment and joy that develops among randomly selected people when they attend and engage in well-organised assembly.

Champions, terminology, taglines will likely just be part of the time, familiarity and personal advocacy it will take to bring deliberative democracy into the mainstream. There’s still far to go to match classical Athens, democracy by lot’s first and last great success: the ancient Greeks believed their extraordinary civilizational breakthroughs were due to their democracy of randomly selected decision-makers. Here and now, on average just 5% of people reached by post or phone to be told they have won the civic lottery to be part of a citizens’ assembly actually say they will join in.

The quest for an ideal

Several deliberative democrat speakers in Brussels are now more comfortable calling themselves part of a movement. Activists share a faith in the ideals of greater participation, the representative power of random selection and the benefits of greater public engagement. But it’s not clear precisely what the movement’s most favoured new constitutional arrangement is.

A draft paper circulated to conference-goers suggested a “system goal” for future discussion and development: “People from all walks of life benefit from more inclusive, fair and informed decision-making on tough, politically-gridlocked issues because lottery-selected deliberations are a go-to decision-making method (institutionalised or not).”

Such dense language reflects the evolutionary approach that most deliberative democracy activists prefer, despite the fact that a system change to democracy by lot would actually be revolutionary. This careful approach is not surprising in a movement that has minimal ideological convictions and is still trying to find its feet. But what did strike me more this year in Brussels than last year in Vancouver – and perhaps it was only because I kept asking people provocative questions – was that younger participants seemed keener to hone a more radical approach to rally round. At the same time, others are convinced a hybrid mix of elected politicians and randomly selected bodies goes far enough as a goal. One reason is that established activists are often concerned about threats to credibility and government funding.

To build participatory democracy into a default attitude in government bureaucracies, argued Democratic Society’s Anthony Zacharzewski, activists need to shift from being “people who are doing experiments around the edge, and thinking about these big new ways of reforming the state, into people who are able to work with the state and work with politics as well … [that means] never quite getting what you want … We may need to grow up.”

Another formulation for a harmonious transition came from Gaetan Ricard-Nihoul, a senior official at the European Commission’s directorate for citizens’ engagement. She said: “We have to show the virtuous circle between voting and the participatory stuff.”

Not every participatory democrat agrees. One UK non-profit, Humanity Project, opposes elections, seeks to create an “assembly culture” from the ground up, and radiates radical urgency. Its website uses a headline font of cutout printed letters more often associated with ransom demands. It recruits citizens for “popular assemblies” that are not chosen through expensive random selection, but from whomever local organizers can mobilise. There is “no need to wait for permission from anyone … Neighbourhood by neighbourhood, we’re building something big enough to change things at every level,” the non-profit says.

At the Brussels workshop on assemblies with no local or national government mandate, University of Westminster academic and author Graham Smith noted that: “Some of us will work with such groups publicly. Others will offer help in private. Others might want to blackball them … We will have different positions on whether to give them support, ignore them or try to kill them off.”

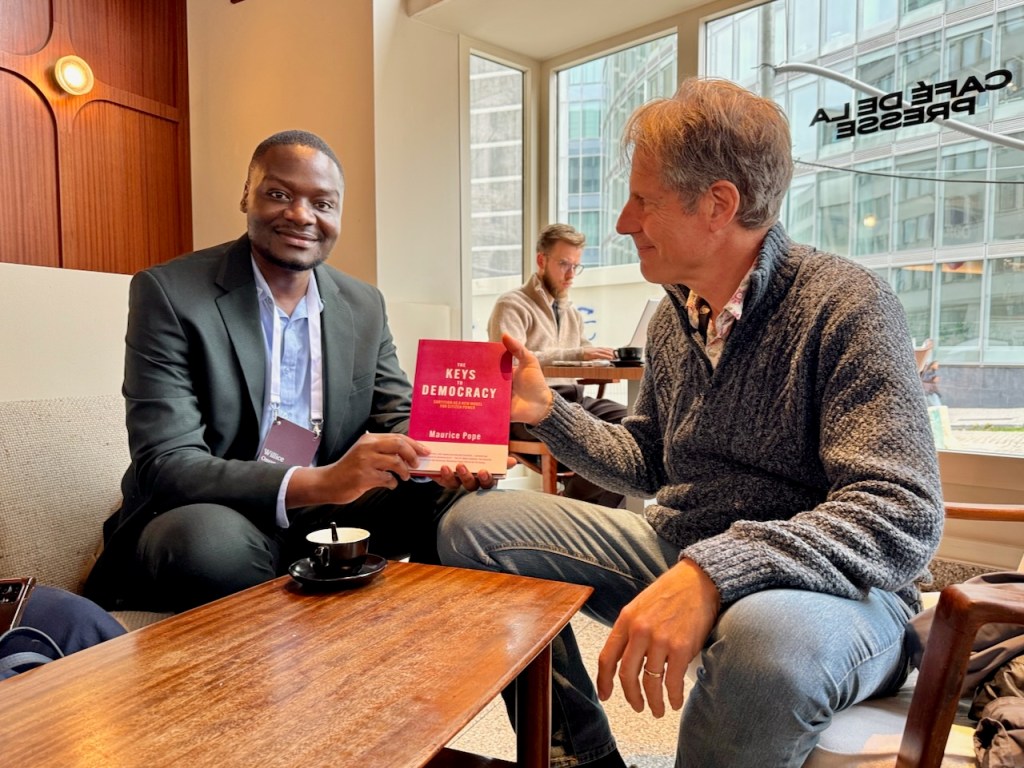

The movement’s lack of clarity over its ambition is no small issue, even for a newcomer to the field like me. I would be disappointed to abandon an eventual goal of a society ruled by a system of pure sortition – even while recognising that this might take another century or so. I became a follower of the movement as I edited The Keys to Democracy, a posthumous book by my late father Maurice Pope, a classicist and admirer of ancient Athens. What convinced me were his arguments about the forgotten power of full, mandatory popular civic engagement and the scientific beauty of randomness.

Brussels: the shining city on the hill?

The more I think of a world without elections, the more conscious I am of a gap in the ideological dimension. It’s not that I would want democracy conferences to resemble a meeting singing hymns to the same religious or ideological belief. That would be impossible anyway: the new democrats’ diversity of approaches and lack of specific ideology is too great. But many deliberative democrats do feel that their cause will make the world a better place, and that a more decisive spirit might get there quicker.

Sortitionists are not oppressed heretics and are unlikely to emulate the 17th century English religious dissidents who boarded the ship Mayflower and headed to the US to build a new world. But I can’t help thinking it would help define what is possible if an organisation, a community, or even a town chose to join an experiment to see what happens if its key public decisions were entirely taken through randomly selected panels or assemblies.

One chapter of my father’s book lays out what a sortition-based utopia might look like. He imagines a scientific community on Antarctica being the only survivors of a nuclear apocalypse that wipes out the rest of the world. The group goes on to repopulate New Zealand with an entirely new political structure. In reality, a more likely candidate to be sortition’s shining city on a hill might actually be Belgium, or more specifically, my own home town of Brussels.

The time seems ripe. Belgium’s national politics are near-paralysed by squabbling parties and multiple governments based on regions and language groups. The electoral gridlock is worst in Brussels, which is both a city and one of Belgium’s three federal regions. It has been unable to form a government for more than 500 days since the last elections in June 2024. Popular confidence in politicians is plummeting.

“Every year we lose between one and 2% of people [in Belgium] still believing in democracy,” David Van Reybrouck said in his speech. “It doesn’t seem a lot, but after 10 years, it’s going very fast.”

Already in 2011, Belgium was left without a national government for more than 500 days after an election. This had inspired Van Reybrouck to lead the organisation of one of the world’s first citizens’ assemblies, the G1000, to try to plot an alternative path forward for the country. Since then Belgium has played a pioneering role in the world of deliberative democracy.

In 2019, Belgium inaugurated the world’s first permanent citizens’ assembly as part of the parliament of the East Belgian German-speaking community. It is made up of two parts: one is permanent in the sense that it chooses the topics for the second part, which are one-off citizens assemblies; the first part’s membership is regularly refreshed with new members. The assembly is now onto its seventh policy topic. In 2023, the Brussels region also created a permanent climate assembly, again the first permanent one of this type in the world, in which a subgroup of the group of 100 randomly selected citizens chooses the topic for the next one. Two other regional Belgian parliaments have refreshed their chamber’s policy committees by mixing in three randomly selected citizens for each parliamentarian. The national parliament has now also agreed that future assemblies that have a government mandate can use the national electoral register for their random selection procedure, considerably reducing the cost of any such exercise.

Random selection is putting down local roots in the city. By chance – of course – my wife Jessica Lutz was chosen by lot to join a panel of citizens from our own sub-district, which meets every three months to adjudicate on projects and priorities for the commune. “Being part of a decision-making structure, with people that I would never otherwise meet, makes me realise how important it is to take everyone’s perspective into account. I also see how when you bring things down to practical decision-making, differences between people aren’t so big. And even though our panel is very small, I see how empowered everyone is by having a say in where our tax money goes,” she told me.

The idea of sortition is becoming mainstream. Alexandre Helson, seventh-generation head of one of Belgium’s fine ginger biscuit makers Maison Dandoy, wrote in the Belgian newspaper Le Soir in October: “What if we [citizens] pick up the baton, after the elected ones have tried for months to find common ground? What if we dared to do a big, participatory citizens’ assembly? [It would] restore confidence and remake democracy into what it should be: the slow construction of a common language.”

In an opening speech to the democracy conference, Fatima Zibouh, a Brussels veteran of the original G1000 citizens’ assembly in 2011, described a city ripe for a new form of governance. She pointed out how different the city is from Belgium’s two main federal states, Dutch-speaking Flanders and mostly Francophone Wallonia. With 40% of Brussels’ population not having Belgian nationality, and 74% having one parent born outside Belgium, it is actually the most diverse city in Europe, she said.

“Radical inclusion is not just being invited to the party or being asked to dance, but helping to design the party, to shape the space itself,” Zibouh said. She has now also called (in an open letter in Le Soir newspaper) for a randomly selected “B1000” assembly for Brussels to think up a citizens-based alternative while politicians bicker on about their next coalition government.

The instinct to cooperate

Whether in Brussels or far beyond, it’s still hard to imagine decision-making citizens’ assemblies being written into constitutions without a major breakthrough in public opinion by the movement for deliberative democracy, a change of heart among political leaders or a much greater availability of resources. Getting approval for advisory ones remains uphill work.

“We are both desperate for money and coming across as a luxury item … how do we communicate the value of what we do better?” Zacharzewski said. “If we are doing this as a collective of fragile organizations, always trying to close the next budget … we will never be able to let our thinking and our work rise to the scale that needs to be at.”

But the movement is growing. New democrats working on new, deliberative ways to channel the human instinct to work for the common good came to Brussels from all over the world. It’s a mostly “northern” movement so far – indeed, richer countries have got a lot to fix with governance at home before preaching to others – but a record tenth of participants came from the global “south” this year.

And despite the high-level reasons for angst, the conference bubbled with presentations about the uptake of citizens’ assemblies in the Balkans, in Africa and in eastern Europe. Adam Cronkright gave a pre-screening of his documentary “Goodbye Elections. Hello Democracy,” a superb fly-on-the-wall account of a US citizens assembly about Covid-19 held online during the pandemic and due for release in 2026. One inspiring participant told of an assembly in Ukraine where the allotted group insisted on going ahead with the meetings in a bomb shelter despite ongoing Russian attacks.

Cooperation has always been a default feature of humankind. Arguably, it’s what made us what my late father would have called the Top Species (so far). Societies have always found ways to channel this instinct through religions, ideologies, or moral codes, as in the Victorian era. Even criminal gangs create rules to collaborate. Authoritarians exploit this tendency too, prioritising themselves and imposing collaboration through force and oppression.

Our democracy conference in Brussels refreshed my conviction that most people actually want to work together in the positive public interest, and long for an agreed, decent way to do so. And that a great group of people is working hard to harness this cooperative instinct as a force for good.

Leave a comment