Few reporters could match the outsize life of Thomas Goltz. He was fearless, unfailingly generous and utterly committed to getting out the news: his version of events, from right up close. He gave an undivided loyalty to any unjustly treated people whose cause he stumbled upon, whether they be Turks, Iraqi Kurds, Chechens, native Americans or the people of Azerbaijan.

The American reporter and writer died on 29 July in Montana after a long illness, aged 68. To some, he may have seemed over-bearing, a maverick or even a recklessly unguided missile; for many more, like me, Thomas will be deeply missed as a unique, funny and loyal friend and story-teller who made a virtue of never accepting any limits.

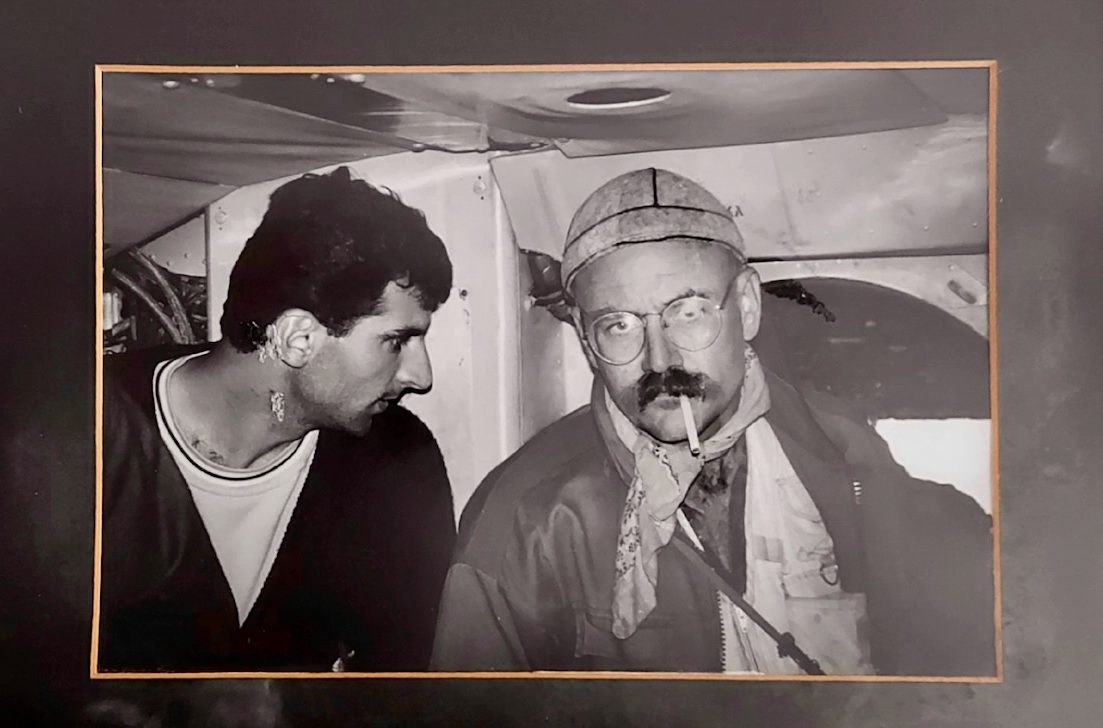

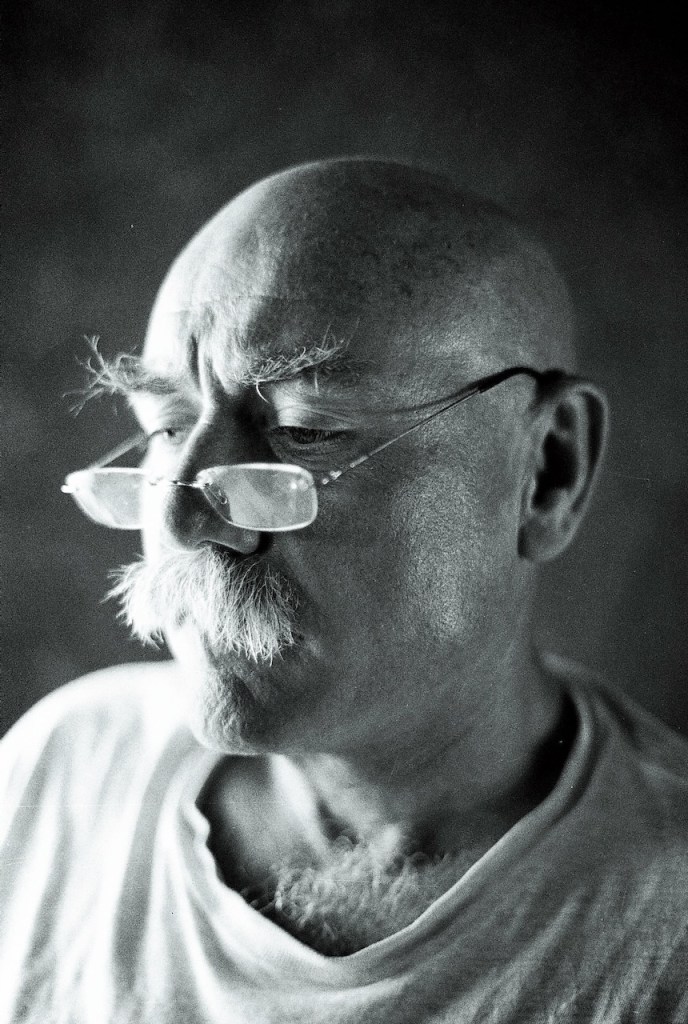

Sporting the bushy moustache of a 19th century German general and topping his smoothly shaved head with a variety of Turkish and Caucasian caps, Thomas was an inimitable, all-in reporter.

Here’s one vignette: during a 1992 moment in the war over Nagorno-Karabakh, an Azerbaijani pilot offered us a flight into a besieged town called Khodjaly. I refused, noting that the helicopter was peppered with fresh bullet holes from the town’s attackers. But Thomas did not hesitate to join a chaotic group of traumatised townspeople for the risky ride back into the maelstrom and impending massacre. I watched him clamber aboard among shopping bags, boxes of ammunition and a canary in a cage, never looking back or having a thought about how he would arrange his return to safety.

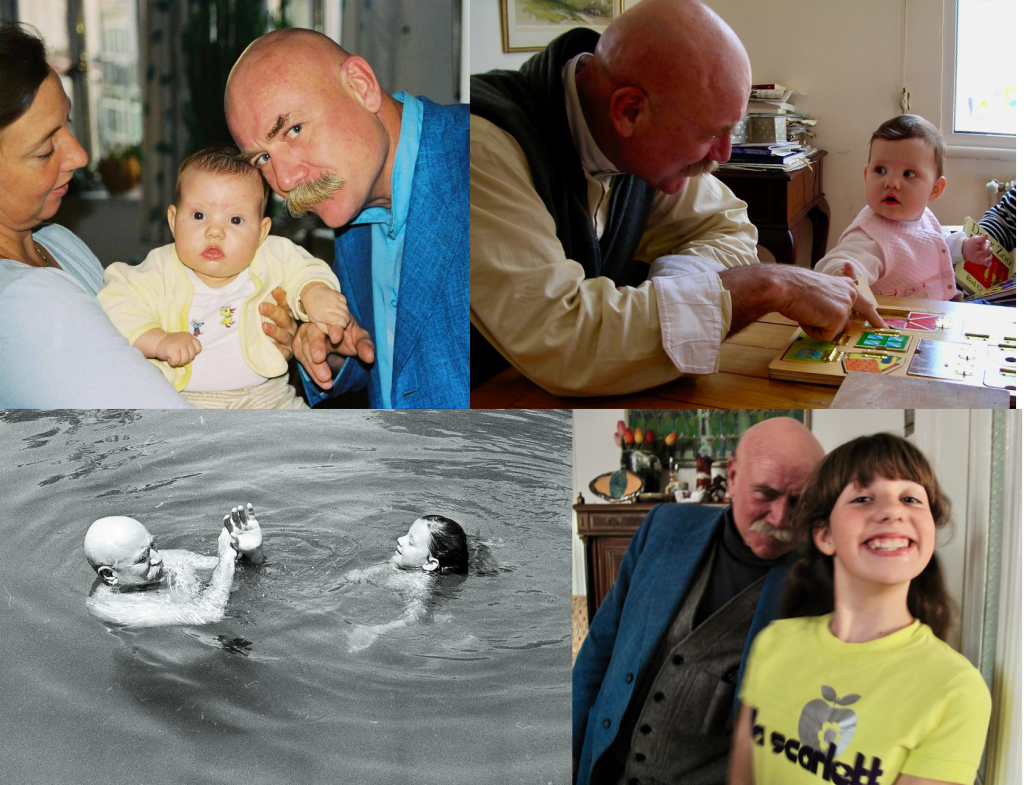

Thomas’s life matched his work. He didn’t just do press-ups, he did them while he was in a handstand, pushing himself up perpendicularly and doing a dozen at a time. He didn’t just write books, they poured out of him, and woe betide the computer keyboard that tried to resist his finger-punching. No good conversation was complete until the volume of his voice had reached that of an amused or outraged outcry.

“I discarded stage acting to embrace real life theatre,” Thomas told Conversations with History, an hour-long interview with Harry Kreisler of the University of California at Berkeley. Luck, fate and simply being the right person with the right skills at the right time in the right place was what propelled him, Thomas said, to give his heart and soul to the chance stories that crossed his path. He was inspired by people resisting unjust, overwhelming force.

“I also sallied forth with the pretence of changing the world,” he told Kreisler. “This is common to many journalists, young and old, that that article that you write, that that television program that you do, will be so effective that the viewer, the reader, will stand up and shout: ‘Stop, stop this war! Stop this madness!’ …. Otherwise, it would be almost impossible to do your job in these extremely difficult situations.”

I first met Thomas when he was one of the only American reporters working out of Ankara, Turkey, in its isolated, post-military coup era of the late 1980s. I remember raucous evenings with him and his thoughtful and equally determined Turkish wife Hicran, a doctor. She was to share several of his adventures in far-flung places and stuck by him to the end, despite his solitary exploits and the self-destructive drinking that interspersed them. I regret – having enjoyed his unaccompanied, no-holds-barred riffs on rock singing – that I never saw him perform as part of a foreign correspondents’ band. But I think it’s for the best that he and Hicran abandoned keeping their one-time pets, a plodding crew of un-house-trained tortoises.

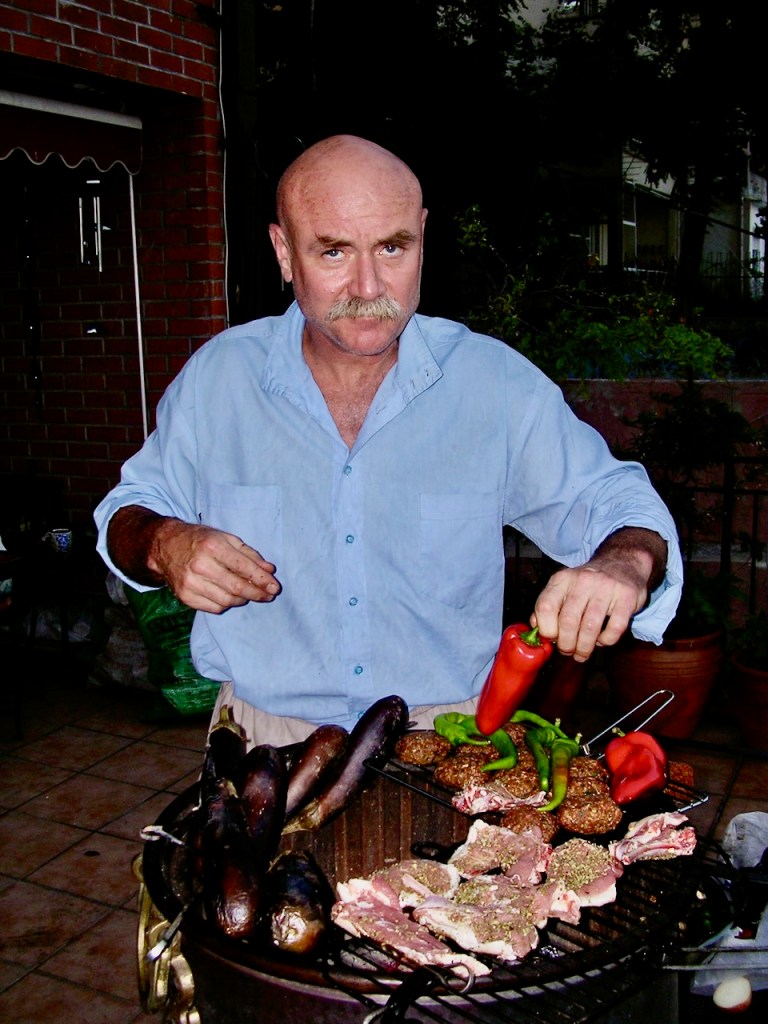

Thomas preferred being a host to being a guest – probably so that he could claim the dominant position of what Georgians call the tamada, or toast-master, leading unending rounds of glasses raised to all and sundry – and was an astonishingly good cook, especially of his trademark dish of glazed and barbecued venison. He rarely missed a hunting season in his adopted home of Livingstone, Montana, and would regularly pass through Istanbul with frozen hunks of deer that he had personally shot and carefully butchered in the Montana woods and hills.

After he moved to the former Soviet Union around 1990, we did much together in the heady early years of independence for Azerbaijan and Georgia. I was the visitor and he was always generous with hospitality, information and contacts. Any rivalry was restricted to my claim to the first outsider to meet the future President Haidar Aliyev, in his native Nakhichevan, back in October 1990; Thomas’s that a year later, he was the first outsider to take a news photograph of the founder of what became Azerbaijan’s ruling dynasty. During our frightening visits to the chaotic front lines of the war over Nagorno-Karabagh, Thomas was always out in front.

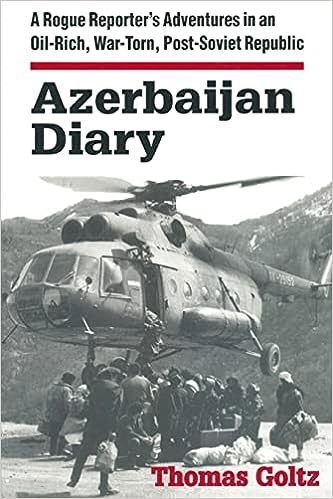

Thomas treasured his finalist’s place in the 1996 Rory Peck awards for his one-person video diary about Russian attacks on a Chechen village, Samashki, and the consequences for its people. He was also thrilled to be given an honorary doctorate recognizing his advocacy on behalf of Azerbaijan, which started long before it became an oil-rich state. He would also have been proud of a glowing obituary in The Caspian Post and an encomium from Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, who said “the articles, books he wrote and films he made about the Armenia-Azerbaijan Nagorno-Karabakh conflict … made an invaluable contribution to conveying the true voice of Azerbaijan to the world.”

Thomas brushed aside any cricitism about his no-holds-barred embrace of those he reported about. “A journalist is not a perfectly neutral vessel. We pretend this,” he told Harry Kreisler. “When someone is feeding and protecting you and housing you by definition this will engender loyalties and a certain spin or twist. [There should be] a profound sense of responsibility to one’s subject. There’s no ‘wham, bam, thank you, ma’am’ …. The overriding lesson must be that you, O journalist, must take responsibility for having been there.”

Books followed his reporting, accompanied by his often excellent photographs. The Caucasus inspired Thomas’s trilogy of ‘Diary’ books on Azerbaijan, Chechnya and Georgia, to which he later added a collection of essays on Türkiye (Turkey). An unfortunately lightly-edited collection of his essays on his years in the Middle East, Zakhrafa, includes tales of his hair-raising encounter with a dissident fellow patient in a Damascus hospital who knew he was about to be killed and his offbeat months as a self-appointed relief worker in Iraqi Kurdistan. My favourite is his Assassinating Shakespeare, an account of his overland journey aged 21 from Berlin to Cape Town earning money part of the way doing (as ever) one-man shows with wooden puppets representing Romeo and Juliet, Othello or King Lear.

Unusually among reporters, Thomas was also a passionate American patriot. He loved his country, his family from North Dakota, his home and friends in Montana, and would have liked nothing better than to serve the national interest. One of the deep disappointments of his life, he once told me, was how the onset of troubles in his nervous system ultimately ruled out his offer to work alongside U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

Whether Thomas’s outspoken, outsider style would have lasted long in any official institution is questionable. His bust-ups with newspaper employers were legendary, often after long phone calls in which he excoriated his editors for not sharing his sense of critical urgency.

Paradoxes abounded elsewhere. Thomas thought telling the story was far more important than any financial reward, yet would anger at how hard it was to get paid. He was a gorgeous writer, but skimped when it came to the critical work of editing. He longed for public applause, but sometimes had difficulty adapting to what his audience was ready to hear. He was an individualist unwilling to travel with translators or what he called the hack-pack, yet he wanted to convert the mainstream to his views.

Above all, he threw himself into danger as a war correspondent, while hating the likely pointlessness of risking his life.

“A whole string of people have run up against the brick wall of impossibility, the futility of … changing the world with that one article, or that television program,” he told Harry Kreisler. “At that point you wonder if you are only being an entertainer and that violence is your tool to entertain.”

Wherever you’ve gone now, Thomas, I’m sure you’re entertaining them still. Nobody will be calling me “Hugolinavitch!” down here any more , but I hope one day I’ll meet you somewhere again to hear that happy cry.

Leave a reply to Tim Cahill Cancel reply