When the news searchlight lit upon Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney last month as the saviour of democracies from US President Donald Trump and right-wing authoritarianism around the world, did it really show us a new path forward?

Or did the Canadian ex-central banker’s well-turned speech at Davos just offer a sleeker retread of the same system of politicians, parties and elections that has gotten us all so badly stuck in the first place?

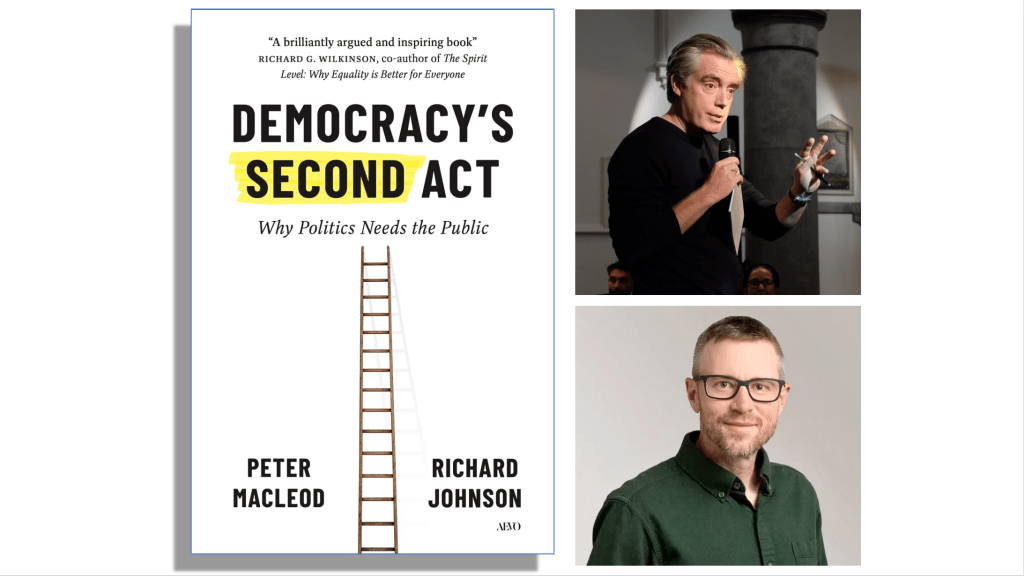

For the most up-to-date presentation of a real alternative – more deliberative democracy, using tools like citizens’ assemblies – I highly recommend an even more eloquent work by two other Canadians. Peter MacLeod and Richard Johnson have spent decades between them to shape and improve a better form of public governance and decision-making.

Serving powerful interests

In Democracy’s Second Act: Why Politics Needs the Public, published by University of Toronto Press on 7 February 2026, MacLeod and Johnson set out how purely electoral representation is reaching the end of its useful time. Building on the wisdom of ordinary people, their book tracks how far the movement for deliberative democracy and citizens’ assemblies has developed as a plausible answer to the new needs of human progress.

“The achievements of modern democracy should be celebrated, but we can’t pretend they are the complete and final expression of our democratic potential,” the two men write. Today’s public decision-making systems “didn’t evolve by accident. They serve powerful interests – political, corporate, and bureaucratic – that benefit from keeping control concentrated and the public at a distance.”

MacLeod and Johnson are not academics or ideologues. MacLeod in particular has deep experience of electoral politics. Both are seasoned professional organizers of citizens’ assemblies. Indeed, MacLeod’s roots go back to the first use of a modern citizens’ assembly in Vancouver in 2004.

Experience, detail, documentation

They lay out their argument with a wealth of personal experiences, unexpected examples from all walks of life, well-chosen historical detail and original documentation. Chapter by chapter, they

- Survey public dissatisfaction with the status quo of electoral politics;

- Look carefully at whether the public is ready to take on more;

- Detail the success of randomly selected assemblies that led to breakthroughs in Ireland on same-sex marriage and abortion;

- Gauge the limits of both citizens and citizens’ assemblies;

- Show how public engagement produces far more satisfactory results than opinion polling. As they put it, “simply ‘liking’ something is just a small part of the equation”, when public opinion is necessarily remarkably fluid;

- Give examples from Sweden, Canada and the US to show how ordinary people are good at learning about issues; how private initiatives can outdo official action, from integrating refugees to measuring radioactive fallout; but how the state must have a role in keeping facts straight;

- Share lessons from Denmark, the US and beyond about how usefully people form cooperative associations and worker-owned companies.

The arguments and narrative arc are, naturally, somewhat similar to other leading non-academic books that advocate for citizens’ assemblies: the pioneering Against Elections (2013) by David Van Reybrouck, the polemical An End to Politicians (2017) by Brett Hennig, and the utopian The Keys to Democracy (2023) by my own late father Maurice Pope. Coming soon too will be Politics without Politicians by Hélène Landemore, to be published by Penguin on 10 February 2026, and bringing a unique, eye-opening focus on France’s 2022-23 citizens’ assembly on assisted dying.

Democracy’s Second Act does not suggest a new overall roadmap or any grand new constitution as a destination. The book dodges the question of whether or not citizens’ assemblies can or should actually take charge, saying “assemblies do not claim the power of legislation, regulation, executive authority, or judicial interpretation of the law, but neither do they shrink from their role of representing the public in critical questions of policy.”

Instead, the authors are more concerned to popularise a new generation of democratic principles, wherever they may lead, and to strengthen “democratic fitness … the muscle memory of agency”. Indeed, the book stands out for its global perspective and tellingly researched examples from the wider movement for deliberative democracy, sortition and citizens’ assemblies. Above all, there are concise illustrations from mainstream history and culture that show the tension between participatory democracy and top-down rule.

Too lazy and ignorant?

Take the old prejudice that people are too lazy and ignorant to take or even want a real role in government, and that experts are therefore those best suited for the job. The authors show how exactly that fits into the contrasting 20th century approaches of US journalist Walter Lippmann and philosopher John Dewey: “one that fundamentally sees the public as a risk to good government; the other believes it’s a resource”. Throughout the book weave in evidence for how mistaken Lippmann’s formula for top-down rule can be. They also go neatly beyond Lippmann’s skepticism and show that “while they may be no such thing as an omnicompetent citizen, there is yet a possible omnicompetent public“.

Another striking revelation, for me, is their account of the twelve-day-long Putney Debates in England’s mid-17th century political turmoil. This debate between different factions of Oliver Cromwell’s armies pitched constitutional monarchists (“grandees”) and advocates for citizen democracy (“levellers”). The levellers called for freedom and equality before the law, which they hoped to achieve through universal suffrage. MacLeod and Johnson show how these, well before the US and French revolutions, marked the first shoots of the centuries-long arc of “democracy’s first act”.

Nearly four centuries later, this first act has culminated in elected parliaments that have become increasingly powerful. But now voter turnout is going down and alienation is rising. As the authors say, “all across the democratic landscape, past and present, we have found examples of crises in governments and societies that expose a growing gulf between citizens and their elected representatives.”

A bulwark against oligarchy

The time has now come, the authors argue, to transfer agency and participation away from representative parliaments directly to the public at large. “A truly democratic association of citizens … has to fundamentally empower people to propose their own questions, not just provide answers to the ones already asked,” they say. “Democracy … must fundamentally be a two-way street.”

And for that, there needs to be a new way of thinking about the public, trusting ordinary people rather than elected politicians, even if they are as charismatic as Mark Carney. “A randomly selected, deliberative and representative public, as a citizens’ assembly seeks to create,” the authors say, “is perhaps democracy’s greatest bulwark, in the modern age, against the slide into oligarchy.”

Leave a comment