First sparks can be hard to fan into bright lights. Especially when they’re needed to banish dark demons lurking in the violent history of Iraqi Kurdistan’s six million people.

Five years ago, a few Iraqi Kurdish health professionals and friends of Iraqi Kurdistan, mostly in Britain, had an idea. They wanted to introduce the first psycho-therapeutical help for such deeply buried traumas. They knew that few Kurds even consider having such treatment. The little relief available is mostly tranquillisers or heavy-duty psychiatric medicine.

The Iraqi Kurdish expatriate group faced an uphill battle to introduce this “talking cure”, which consciously shapes behaviour to leave trauma behind. Western partners hesitated to deliver a program in a remote place where their governments advise against travelling. Hopeful leads for funding came to nothing, even after apparently unbreakable promises. Kurdish politicians voiced support, but were overwhelmed by other priorities.

Bringing the plan together

Yet the original core group – collected under the umbrella of a charity, KR-UK-Impakt – kept the idea alive with stubborn persistence. And gradually the pieces of their plan began to come together.

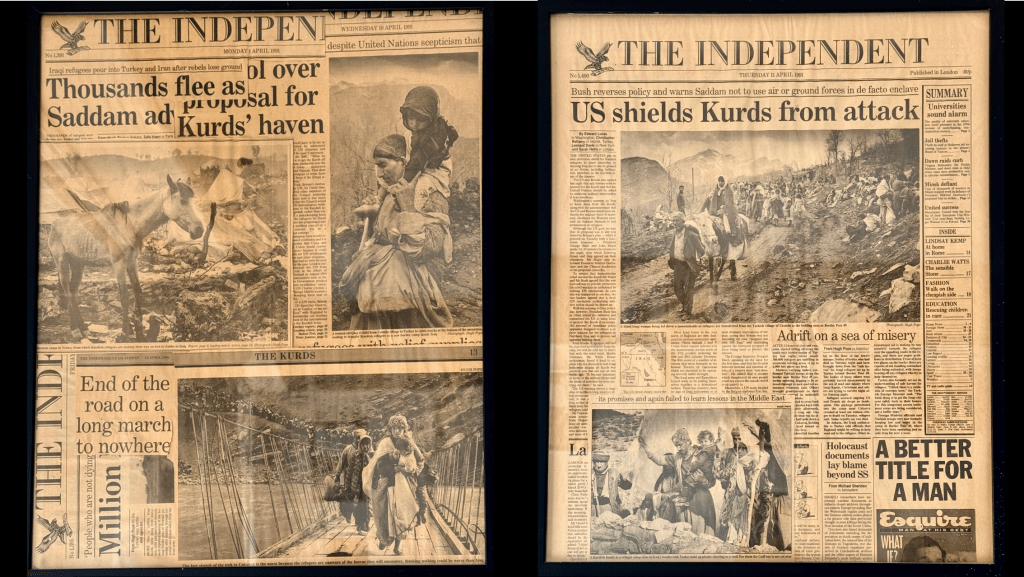

An anonymous donor stepped forward in the name of foreign reporters who travelled to witness the doomed Iraqi Kurdish uprising in March 1991, when U.S.-led forces reversed the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait.

An Iraqi Kurdish host offered to host the program. The European Technology and Training Centre (ETTC) in the regional capital of Erbil brought immaculate organisation, facilities and the ability to choose qualified candidates.

To actually teach the new method, the Oxford Cognitive Therapy Centre (OCTC) put up its hand. Its coaches found ways to train therapists online, in English and with no personal meetings. Teachers even had to judge their students’ clinical abilities from videos of them with patients. For these leading UK experts, the work was a rare chance to experience how Cognitive Behavioural Therapy would fare in a non-Western context.

An emotional launch

Despite all the difficulties, 30 candidates were found who had the right knowledge of English and psychological training. They gathered for the launch of the Kurdistan Mental Health Program in January 2024 with emotional speeches from all involved. Just the night before, a dozen Iranian missiles had struck what Tehran called “Israeli targets” in northern Iraq, killing four Kurds not far away from the conference room in Erbil.

“Sometimes, as the Kurdish people, we see these tragedies as normal,” Zakia Saeed Salih, minister of social and labour affairs in Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government, told the opening ceremony. “But they have left a long-lasting impact.”

To illustrate her region’s legacy of more than a century of conflicts, Salih told the candidates a story she had heard from Jonathan Randal, a veteran Washington Post reporter. Randal had challenged one of Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders, Jalal Talabani, to take some care of a rare survivor in a village hit by the Anfal, or late Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s brutal massacres of Iraqi Kurds in the 1980s. “Why?” Talabani replied. “We have all been through that. We have all survived it. We all need therapy.”

Even after the therapy training started, the problems weren’t over. Language obstacles proved insuperable for some. Family obligations intervened. Electricity supplies and the internet broke down. Despite the lifting of sanctions, Western banks remained suspicious of Iraq and financial transfers were delayed up to one year. Lack of new funding meant that a planned second cohort of candidates was never recruited. Instead, attention was focused on giving a second year to the original students, to make sure all reached the required proficiency.

Graduation

It all seemed worth it on 15 December 2025, when a first cohort of proud Iraqi Kurds received their certifications from the Kurdistan regional government minister who had greeted them at the start. There 30 therapists and clinicians who completed either one or two years of training and then supervision. 12 made it to Erbil to receive their final certificates.

During the previous five years, the idea born in 2020 had brought together at least 50 people, absorbed a mountain of volunteer hours, and had cost half a million dollars. With matters like official accreditation of program graduates by the Iraqi authorities still a work in progress, it may be decades before anyone can plausibly guess how much therapy alleviates Kurdish trauma.

But it is a start. The graduates spoke movingly of their determination to make the most of their new insights, whether in public health or their private practices. Media coverage alerted the population to the new approach. Salih, the Iraqi Kurdish minister, promised continued interest and support.

A candle of hope

Jonathan Randal, speaking to the ceremony as one of the outside reporters who had witnessed the 1991 turmoil, told the trainees how the money was donated to thank the Kurds and their leaders for smuggling them alive over the border into Turkey. The journalists escaped not far ahead of the Iraqi army that brutally crushed the rebellion and killed one of those reporters, German photojournalist Gad Gross, and his Kurdish fixer, Bakhtiar Abdulrahman. A three-person BBC reporting team also died on the Iraqi-Turkish border around the same time, apparently murdered by smugglers.

“I hope what you have learned will be a candle of hope in these dark times, and that the knowledge you have obtained will light many more candles in the future,” Randal told the newly qualified therapists..

December’s graduates will be the last cohort for now. Hopes for new funding had centred on an Iraqi Kurdish institution that has now been crippled by the big 2025 cuts in U.S. foreign aid. But KR-UK-Impakt is still seeking money for a Phase II of the Kurdistan Mental Health Project.

A new London play

Outside moments of catastrophe, it’s hard to raise awareness of the region’s long term struggle. The co-founder of KR-UK-Impakt, Chris Bowers, a former UK consul-general in Erbil and BBC journalist, has done so by writing a new play about Iraqi Kurdistan, Safe Haven. The play runs from 14 January to 7 February 2025 at the Arcola Theatre in London. Set in the corridors of British officialdom, the play shows how the UK helped create a protected area for the Iraqi Kurds after 1.5 million of them fled their homes in terror.

“It is a dramatic story of a few people in the right place doing the right thing at the right time,” Bowers said in an interview about the play with Theatre Weekly.

I was one of the reporters who watched the Iraqi Kurdish refugees pour over the Turkish border. So it’s moving to see Arcola Theatre putting my photos from those freezing mountain passes to good use on stage, in the posters and in a small exhibition at the theatre during the run. Kurdistan24 television did a nice report on the play that you won’t need Kurdish to understand.

The Iraqi Kurdish emergency was not the first and is far from the last wrenching displacement of people in the world. The UN says a total 36.4 million people now count as refugees who have fled over international borders, and 73.5 million count as internally displaced. That’s 117.3 million people forced out of their homes, five times as many people as in 1991.

The people involved will not be the only ones who suffer. If these traumas remain untreated, the chances are that their communities will be trapped in yet more cycles of violence.

Correction: The number of students in the first cohort of the Kurdistan Mental Health Program was corrected on 11 January: 12 students received their certificates in Erbil, as originally stated, but altogether 30 were trained for either one or two years.

Leave a comment