Set between Istanbul and London, dancing over more than a century, hovering between fact and fiction, Andrew Finkel’s debut novel is connoisseurs’ delight. Jewels glimmer, capes swirl and mother-of-pearl inlay glistens from every page of The Adventure of the Second Wife: the Strange Case of Sherlock Holmes and the Ottoman Sultan. A deep and easy familiarity with life in Ottoman Turkey is interleaved with Sherlock Holmes in shape-shifting exploits. The complexity of the overall story is a minor masterpiece in itself.

In the end. there is a solution to the mystery at the heart of the book. Or is there? Each time I try to fit the book’s narrative together, it seems to come out slightly differently. It’s like a truth about the sprawling metropolis of Istanbul that Finkel shares early on in the story:

I would say that to understand this story you also have to understand Istanbul, but I am not convinced such a thing is possible. I do not pretend the city is Eastern and inscrutable. In many ways it is friendly and familiar. But it is devious, like the pub raconteur who, while you work out if he is spinning a tale, has you buy him another round. On each visit I made, I felt I had come to a different place. It was like watching a time-lapse kaleidoscope of urban sprawl. Istanbul is a city where things change with a whir, and where standing still feels like falling through air.

When I finished The Adventure of the Second Wife, I went through some passages again so I could appreciate the text with new knowledge. I wasn’t sure that I’d understood the role of all the characters, even if all the loose ends seemed tied up. A tricky trompe-l’oeil is that the story feels so authentic: one could read it thinking that it was all historical fact. But I felt a certain bewilderment since – when I thought it through – some twists in the plot simply could not be real. It’s actually impossible to see the joints between fact and fiction, like the immaculate marquetry Finkel has us believe that the last great Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II conjured up for his private office.

Forced into the harem

Indeed, history books say that Abdulhamid was a skilled carpenter – but was he that good? I’m almost ready to believe it, because Finkel’s account of Abdulhamid’s inner brooding, off-the-cuff kindnesses and occasional cunning cruelties are so compellingly imagined. He describes a man happiest with his Belgian mistress as a young prince, but who finds himself as sultan “forced to to reject bourgeois monogamy for an oriental harem.” Abdulhamid is always a target of assassination and obsessed with his network of spies. But he is taken aback when his private voicing of approval to one woman for her particular “amatory skill” spreads to all the palace women, who assume he wants the same. This surprise came even though he “knew full well that his nocturnal wanderings had to be recorded for dynastic purposes.”

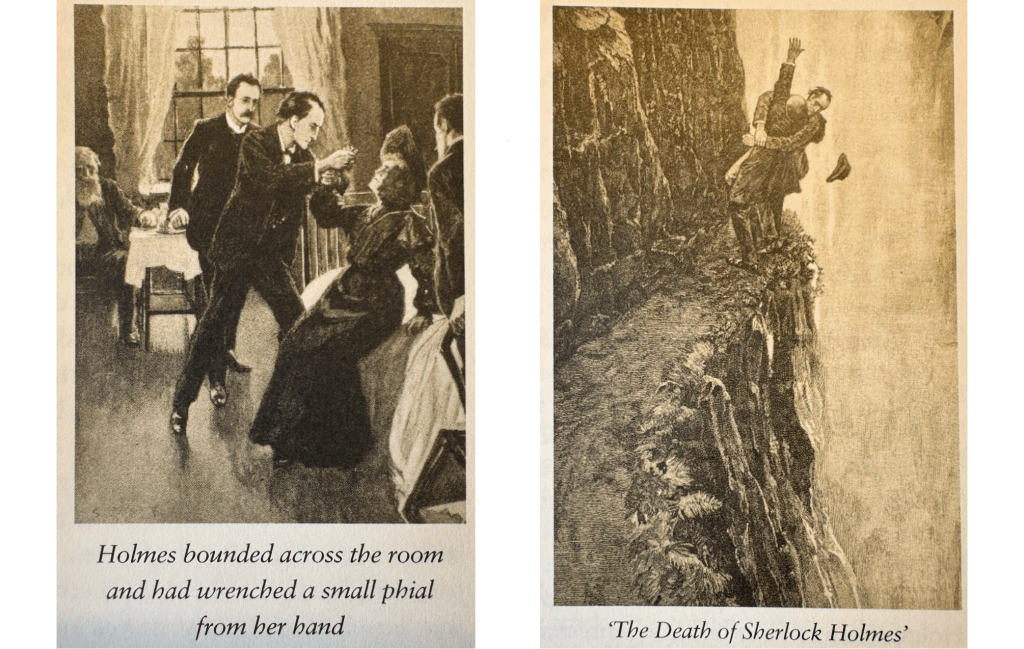

Sultan Abdulhamid II is only the most memorable of the many characters who lingered in my mind after I closed the book. I can’t remember when I last read an original story about Sherlock Holmes, the great 19th century fictional detective, and the original Dr Watson, his loyal sidekick and chronicler. So it was a surprise to get to know a key collective character that is a mainspring of the novel’s action: a global network of fans of the two sleuths, constantly hungry for new insights into their heros, and their creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Finkel also gives us a modern Dr. Watson who leads us through much of the narrative, whose flaws, erudition and ancestry eventually make him fully part of it. And of course there is a train of Ottoman princesses who blend into one another at the heart of the story, damaged, melodramatic, yet each putting their own stamp on a role they had not sought.

Sifting the evidence

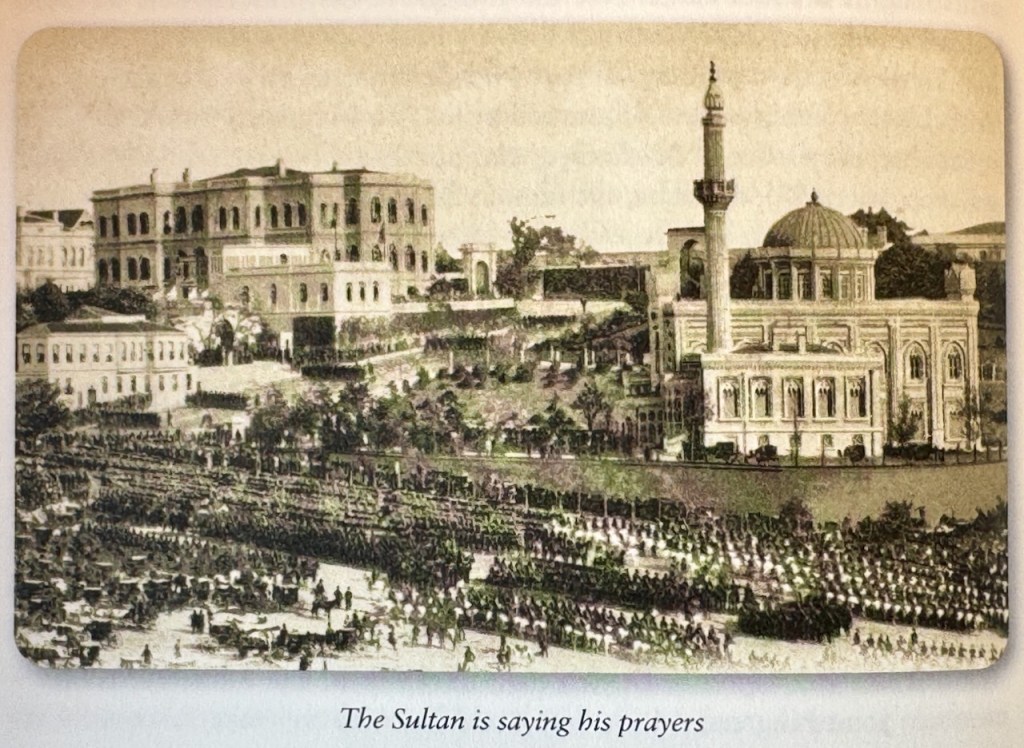

The format of the novel is refreshing, too. The story unfolds through the eyes of multiple characters giving testimony, writing short stories, translating articles and voicing parts of the narrative. They are interleaved with beguiling photographs of remnants of Ottoman Istanbul, illustrations from 1890s London magazines and picture postcards of the era, which all serve to confuse and confirm the factual and quasi-factual foundations of the novel. The hardback is lovingly designed and produced by publishers Cornucopia/Even Keel, adding to the pleasure of the read.

Indeed, the multifaceted timeline and people with more than one name make it hard at times to remember all the characters, as when you open a new puzzle and are overwhelmed by a sea of look-alike pieces. Concentration and a readiness to sift evidence – of course – can be needed to understand completely who’s who on first encounters. But as with looking into the movement of a grand watch, one can pause, work out where the action is going and pick up momentum again, while still admiring the clever complication.

Another pleasure that kept me moving forward is that Finkel’s writing is splendid, especially the take-no-prisoners wit of the dialogue. Innumerable insights into life and people range from an angry outburst by a Turkish professor “unused to being contradicted” to an English housewife happy that her husband studies the minutiae of Sherlock Holmes, since it’s “the sort of pastime that men are meant to have to stop them getting underfoot.”

The power of complexity

Finkel is a long-time follower of Turkish politics (and, full disclosure, an old friend from my days on the Istanbul journalistic beat) and he likes to juggle with what he calls the “power of complexity and the complexity of power.” In one memorable passage, a soldier is posted in an Ottoman palace to guard Abdulhamid after the sultan’s dethronement in 1909, but goes off limits, finds himself in a dark room and is offered a light for his cigarette – and discovers he is alone with the ex-ruler.

The soldier nearly choked on his own smoke. What was he to do? By rights he should have summoned the officers outside, but then he would have to explain his own presence in the room. He had become a partner in the Sultan’s crime. ‘To own the man, give him something to steal’ is the proverb and a roundabout way of saying that leading a man into temptation is a surer means of securing his loyalty than having him swear a flowery oath of allegiance.

I admired too the connections that Finkel weaves through the book: the links between Ottoman Turks, British Victorians and the Indian part of their empire; the strands of continuity in Turkey, from the universal Islamic caliphate to the secular national republic that formed on its core after 1923; Ottoman Constantinople morphing into modern Istanbul; and more universally, the conjecture that the world’s whole population can be divided into either more active Sherlocks or more passive Watsons.

By the end of the tale, a new world had opened up for me in which “the Game” of a Holmesian investigation is always afoot, ready to dart in a new direction. The dark-bearded Abdulhamid II of many a stiff black and white photograph had come to satisfyingly to life. I even felt at home with the likes of a “professional courtier” who is “like an executive happy to serve Coca-Cola today or Pepsi tomorrow … equally at home in Buckingham Palace as … in Yıldız Palace or on a mission to the Emir of Afghanistan.”

What a remarkably original book!

Leave a comment