Where did my late father get the idea that random selection could fix our broken politics? This is one of the most frequent questions I’ve been asked after working on editing Maurice Pope’s book The Keys to Democracy: Sortition as a New Model for Citizen Power, published in March.

As far as I know, when my Dad was writing the book in the mid-1980s, he knew of nobody else working on sortition, that is, deliberation and decision-making by randomly selected, ordinary citizens. (In fact, there were some, but in those pre-internet days few of them knew each other either). He was a diligent scholar and he would surely have cited anyone he’d heard of on the same track.

So I could only look back in his own work. And after publication of The Keys to Democracy, Prof. Josine Blok, a former colleague of my father’s pointed out his 1988 academic paper “Thucydides and Democracy“. The paper contradicts traditional arguments that the meticulous classical Greek historian took the side of oligarchy and (to me, at least) proves its thesis that Thucydides “is not a hostile witness to democracy.” My father openly sides with (ancient, sortition-based) democracy, stating that “indeed, I believe in it.” Already in his 1976 book The Ancient Greeks: How they Lived and Worked, he had launched a robust defence of Athenian democracy against its “scornful dismissal” by mainstream academic experts.

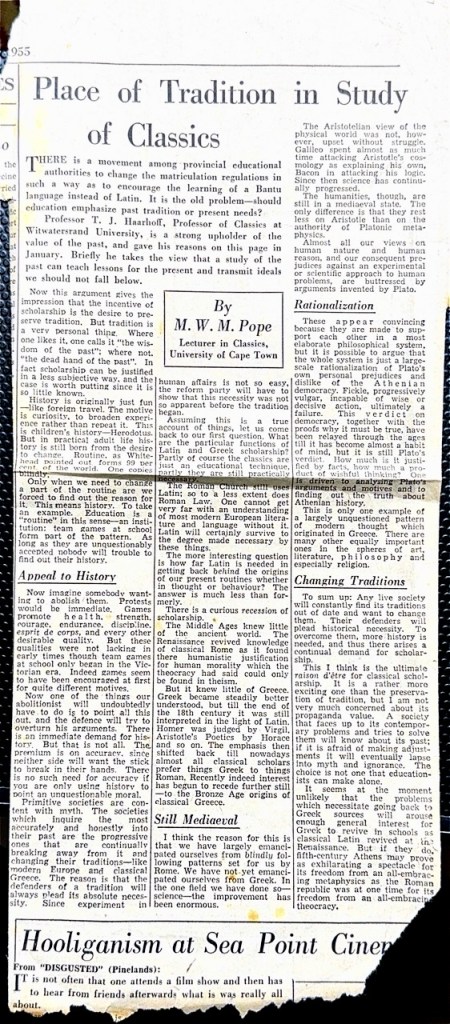

But his convictions dated even further back. Recently, sifting through his papers prior to sending them on to the archives of Cambridge University’s Department of Classics, my mother chanced upon an essay from 1955 in which my Dad voices many of the same points of view. In this opinion article published in the Cape Times of South Africa about the teaching of Latin – he was then a professor at Cape Town University – he is clearly already rehearsing the pro-sortition themes that reach full bloom in The Keys to Democracy.

This text is taken from his best draft. I have only added the Cape Times’ headline, a little punctuation and some context/missing words. There’s an explanation of his time in South Africa here.

+++++

Place of tradition in study of classics

By Maurice Pope

“There is a movement among [South African] Provincial Educational Authorities to change the matriculation [exam] regulations in such a way as to encourage the learning of a Bantu language instead of Latin. It is the old problem: should education emphasise past tradition or present needs? Professor Haarhoff is a strong upholder of the value of the past, and gave his reasons on this page in January. This was some time ago and I do not want now to analyse them. Briefly, he takes the view that a study of the past can teach lessons for the present and transmit ideals we should not fall below.

“Now this argument gives the impression that the incentive of scholarship is the desire to preserve tradition. But tradition is a rather personal thing. If one likes it, one calls it ‘the wisdom of the past’; if not, ‘the dead hand of the past’. In fact, scholarship can be justified in a less subjective way, and the case is worth putting, since it is so little known.

“History is originally just fun – like foreign travel. The motive is curiosity, to broaden experience rather than repeat it. This is children’s history – Herodotus. But in practical adult life, history is still born from the desire to change. Routine, as [philosopher Alfred N.] Whitehead pointed out, forms 99% of the world. One copies blindly. Only when we need to change a part of the routine are we forced to find out the reason for it. This means history. To take an example, education is a routine in this sense, or an institution. Team games at school form part of the pattern. As long as they are unquestioningly accepted, nobody will trouble to find out their history.

“Now imagine somebody wanting to abolish them. Protests would be immediate. [People would say that] games promote health, strength, courage, endurance, discipline, esprit de corps and every other desirable quality. But these qualities were not lacking in early times, though team games at school only began in the Victorian era. Indeed, games seem to have been encouraged at first for quite different motives. Now, one of the things our abolitionist will undoubtedly have to do is to point all this out. The defence will try to overturn his arguments. There is an immediate demand for history. But that is not all. The premium is on accuracy, since neither side will want the stick to break in their hands. There is not such need for accuracy if you are only using history to point an unquestioned moral.

“Primitive societies are content with myth. The societies which enquire the most accurately and honestly into their past are the progressive ones that are continually breaking away from it and changing their traditions – like modern Europe and classical Greece. The reason is that the defenders of a tradition will always plead its absolute necessity. Since experiment in human affairs is not so easy, the reform party will have to show that this necessity was not so apparent before the tradition began.

“Assuming this is a true account of things, let us come back to our first question. What are the particular functions of Latin and Greek scholarship? Partly, of course, the classics are just an educational technique. Partly, they are still practically necessary.

“The Roman Church still uses Latin; so to a less extent does [Rome]. One cannot get very far with an understanding of most modern European literature and language without it. Latin will certainly survive to the degree made necessary by these things. The more interesting question is how far Latin is needed in getting back behind the origins of our present routines, whether in thought or behaviour? The answer is: much less than formerly. There is a curious recession of scholarship. The Middle Ages knew little of the ancient world. The Renaissance revived knowledge of classical Latin, as it found there humanistic justification for human morality, which the theocracy had said could only be found in theism. But it knew little of Greece. Greek became steadily better understood, but [even] at the end of the 18th century it was still interpreted in the light of Latin. Homer was judged by Virgil, Aristotle’s Poetics by Horace and so on. The emphasis then shifted back until nowadays almost all classical scholars prefer things Greek to things Roman. Recently, indeed, interest has begun to recede further still – to the Bronze Age origins of classical Greece.

“I think the reason for this is that we have largely emancipated ourselves from blindly following patterns set for us by Rome. We have not yet emancipated ourselves from Greek. In the one field [we] have done so – science – the improvement has been enormous. The Aristotelian view of the physical world was not however upset without struggle. Galileo spent almost as much time attacking Aristotle’s cosmology as explaining his own, Bacon in attacking his logic. Since then, science has continually progressed.

“The humanities though are still in a mediaeval state. The only difference is that they rest less on Aristotle than on the authority of Platonic metaphysics. Almost all our views on human nature and human reason – and our consequent prejudices against an experimental or scientific approach to human problems – are buttressed by arguments invented by Plato. These appear convincing because they are made to support each other in a most elaborate philosophical system.

“But it is possible to argue that the whole system is just a large-scale rationalisation of Plato’s own personal prejudices and dislike of the Athenian democracy as fickle, progressively vulgar, incapable of wise or decisive action, ultimately a failure. This verdict on democracy, together with the proofs why it must be true, have been relayed through the ages until it has become almost a habit of mind. But it is still Plato’s verdict. How much is it justified by facts, how much a project of wishful thinking? One is driven to analysing Plato’s arguments and motives, and to finding out the truth about Athenian history.

“This is only one example of a largely unquestioned pattern of modern thought which originated in Greece. There are many other equally important ones in the spheres of art, literature, philosophy and especially religion.

“To sum up: any live society will constantly find its traditions out of date and want to change them. Their defenders will plead historical necessity. To overcome them, more history is needed and thus there arises a continual demand for scholarship.

“This, I think, is the ultimate raison d’être for classical scholarship. It is a rather more exciting one than the preservation of tradition, but I am not very much concerned about its propaganda value. A society that faces up to its contemporary problems, and tries to solve them, will know about its past; if it is afraid of making adjustments, it will eventually lapse into myth and ignorance. The choice is not one that educationalists can make alone.

“It seems at the moment rather unlikely that the problems which necessitate going back to Greek sources will arouse enough general interest for Greek to revive in schools as classical Latin revived at the Renaissance. But if they do, fifth-century Athens may prove as exhilarating a spectacle for its freedom from an all-embracing metaphysics as the Roman republic was at the time for its freedom from an all-embracing theocracy.”

++++

For me, this essay shows that my father was into random selection from the beginning of his working life. And at least by his late 20s, he had developed a mission to push back against Platonic ideas, if not Plato himself. Or as my Mum puts it: “your father was always talking about sortition.”

In Chapter 8 of The Keys to Democracy, ‘In Defence of Randomness’, he makes his main attack on Platonic or ‘noumenalist’ ideas. This doctrine holds that true reality can only be found in ‘noumena’, or things that exist in themselves and can be understood only by intellectual intuition, without the aid of the senses. Overturning this philosophy goes the heart of what he was trying to achieve by rehabilitating sortition and putting ordinary citizens in the driving seat. As he put it in The Keys:

The noumenal approach is also covered by the early twentieth-century English mathematician and philosopher Alfred N. Whitehead’s remark that “the European philosophical tradition … is a series of footnotes to Plato.” Its origins go back to the late fifth century BC when the intellectual battle between democracy and oligarchy was at its height. Its political bias is manifest. As soon as we accept that there is a distinction to be made between mind and matter, soul and body or appearance and reality, we can hardly avoid taking sides and assuming that the former of each of these pairs is superior and comes first. Ideas are perfect as ideas, but are spoiled when they are translated into practice. Spirit is pure, flesh is gross and sullied. Knowledge exists (in heaven or in theory) and answers are right or wrong depending on how closely they approximate to that knowledge. These noumenal notions, embedded not only in our philosophy but in our everyday language, encourage a model of society in which wisdom, conferred by knowledge, is the preserve of the few at the top while the many down below have only unorganised desires...

There has only ever been one school of thought that has ever tried to work these attitudes of mind into a coherent system of philosophy, including ethics and metaphysics: that of the Epicureans. They derived the principles of moral conduct from the satisfaction of instinct, which they called pleasure. They accounted for the existence of the world not, as Aristotle had done, by assuming a single prime mover behind everything, but by the opposite, an infinite number of prime movers each endowed with the ability to initiate an infinitely minute spontaneous movement...

… It may be thought that one of the consequences of noumenalism is just as damning to its claim to be taken seriously as the picture of the Epicurean atoms with their unpredictable swerve. The discrimination which asserts that mind is superior to matter can be used to distinguish man from animal, civilised man from savage, sage from fool. It can then be continued within ourselves. Reason, our godlike faculty, can be distinguished from appetite. It can then be asked, whereabouts in us the reason is located: in the heart, in the head, or in some other part? …

… the whole hunt is also absurd. Reason, if it exists at all, must exist not statically in a particular place, but dynamically as the function of an organism. The chase now goes into reverse. Organisms are complex entities themselves and exist within a context of others. There can be no such thing as an organism that functions in isolation. This is true all the way up the scale. There cannot be a brain without a body. The purest philosopher is not independent of his hormones for either the strength or the direction of his thought, nor is he independent of his environment. He is affected by language, time and place, by the opportunities offered by his society and by its constraints. So is everybody. But it works the other way too. For in the shaping of society, all members of it, philosophers and fools, young and old, living and dead, have played or are playing some part, however miniscule.

Furthermore, nobody, whether philosopher, poet, scientist or politician, can tell what is going to influence his thoughts in the next three days or weeks, let alone in the next three or thirty years. All that he can be certain of is that, if he is going to be alive and operational at all, the remarks, writings and actions of other people will be constantly affecting him. He will certainly not be occupied the whole time in making pure deductions from his existing store of experience or (as Bacon put it) in spinning cobwebs out of his own substance. We are all members one of another. We all may affect each other. Such interactions are not confined to human beings. The unforeseen act of an animal, an insect or a wave on a beach may either dramatically or minutely alter the course of our lives.

Seen in this perspective, the Epicurean model of the myriad upon myriad of infinitely small, unmoved movers begins to look less absurd and less remote. It is not obviously less true to reality than the noumenalist one of mind, purpose and knowledge. And when we put flesh on the Epicurean vision and adapt it to the political world, of course it gives a democratic picture. It shows us all the members of a society contributing, each a little, to its total life. In the noumenalist picture, by contrast, the lives of the many have no value except as instruments to execute the designs of the leaders.

[pp. 118-20, abridged]

Can we really blame it all on Plato? I don’t know, but American philosopher Richard Farr wrote a nice, short, skeptical take on the question here.

Leave a comment